It was not until the Khrushchev years that post World War II records were released which cited that “Russia” had suffered 16 million civilian casualties. However, if one looks at the facts, Ukraine was entirely occupied by the German forces for three years whilst only a small part of Russia had been briefly under German occupation during the war. Therefore, it seems reasonable to side with those who argue that Ukraine was the country that suffered the most. Professor Norman Davies criticized western historians when he wrote: “…the overwhelming brunt of the Nazi occupation between 1941 and 1944, as of the devastating Soviet reoccupation, was borne not by Russia but by the Baltic States, by Belarus, Poland, and above all, by Ukraine…nowhere is it made clear that the largest number of civilian casualties in Europe were inflicted by the Soviets” (New York Review of Books, June 9, 1994, p. 23).

The OUN and Dissenters

Since the Government of the Ukrainian SSR had fled the country, there was no Ukrainian government on the territory of Ukraine at the outbreak of the war. As a result, Ukraine was not a collaborator nation of Germany. On June 30, 1941, the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists (OUN), which had been formed years before by a group of dissidents in exile in parts of Western Europe, made an attempt to establish a Ukrainian government. It supported Underground efforts to continue religious and educational programs that instigated Ukrainian nationalism.

The history of the OUN is infected with controversy and confusing political conflict. At the time that World War II broke out, many countries were prone to nationalistic hero-worship. Followers of powerful leaders and outspoken voices were labeled with “-ists” and “-ites” and “-isms,” such as in Francoism, Trotskyites, Banderists, Mel’nykites, and so on. However, the OUN was not a fascist party per se; rather it was built on the principles of nationalism for the sake of freeing Ukraine of her oppressors.

Yevhen Konovalets was the first head of the OUN. In the early to mid-1930s, it was clear that he would have to appoint a successor. Stephen Bandera was the man chosen for the job, though Bandera was already disgruntled about having to take orders from émigrés who—in his opinion —had no idea what was going on in Ukraine. Without approval from those very émigrés, Bandera instigated an act of terrorism in Poland and was shortly after arrested. Because of this, the OUN in Ukraine was brought to its knees and forced to go Underground. Bandera was imprisoned in 1934 in Poland and, during his imprisonment, one of his commanding officers, Lev Rebet, attempted to create a more democratic, less fascist-like organization within Western Ukraine.

Two years later, Bandera was released from prison and, still proclaiming that terrorism and fear were the only way to rid themselves of invaders, asked to meet with Mel’nyk and win back his appointment as leader of the OUN. Neither man recognized the other’s power, and the butting of heads brought absolutely no results. In the meantime, Lev Rebet and another commander, Yaroslav Stetsko, returned to serve under Bandera but attempted many times to initiate a more democratic version of the OUN.

When the Blitzkrieg blew through the borders of Ukraine in 1941, the appointed and recognized head of the OUN was Mel’nyk. However, after the Germans invaded it was Stephen Bandera who surprised the occupiers by ordering Lev Rebet to announce Ukraine’s independence (from Communist rule) in L’viv and appointed Yaroslav Stetsko as Prime Minister. The Germans tolerated it for one week, after which time they disbanded the government and arrested its members. Bandera and Stetsko spent the remaining war years at Sachsenhausen Prison in Germany, under house arrest, while Rebet spent time in prison where he was forced to renounce the declaration. After his release, he eventually fled west in search of his wife and son. Both Stetsko and Rebet spent the rest of their lives shuffling between the two factions, suffering arrests, paranoia, and eventually a murder attempt, which succeeded in killing Rebet in post-war Munich.

Because the Germans were looking for Bandera followers, Mel’nyk —seeing a fleeting opportunity—ordered OUN groups to head into Kiev and announce Ukraine’s freedom. Olena Teliha, a famous nationalist poet, was among one of those groups. The Germans were privy to what was about to happen, however, and those groups were arrested, led to Babi Yar and executed. However, their voices continued to ring from the grave, inspiring thousands of youth to continue the fight. My maternal grandmother and her brothers were some of those young people.

The OUN was formed of both fighting men and women and supported the idea of a democratic and independent Ukraine, but the divergent views between Bandera’s followers and Mel’nyk’s followers had created two factions: the OUN-B and the OUN-M. Each party was forced to go Underground but they turned against one another and fratricide erupted, in the Galician and Vohlyn’ian territories especially. Not only were those Ukrainians faced with the Soviet and Nazi enemies, but they could also no longer trust their own people. Bandera’s band was blackened by propaganda and accusations of committing hate crimes against Ukrainians, Poles and Jews. To this day, in Ukrainian Diasporas around the world, the arguments and bitterness continue to rage.

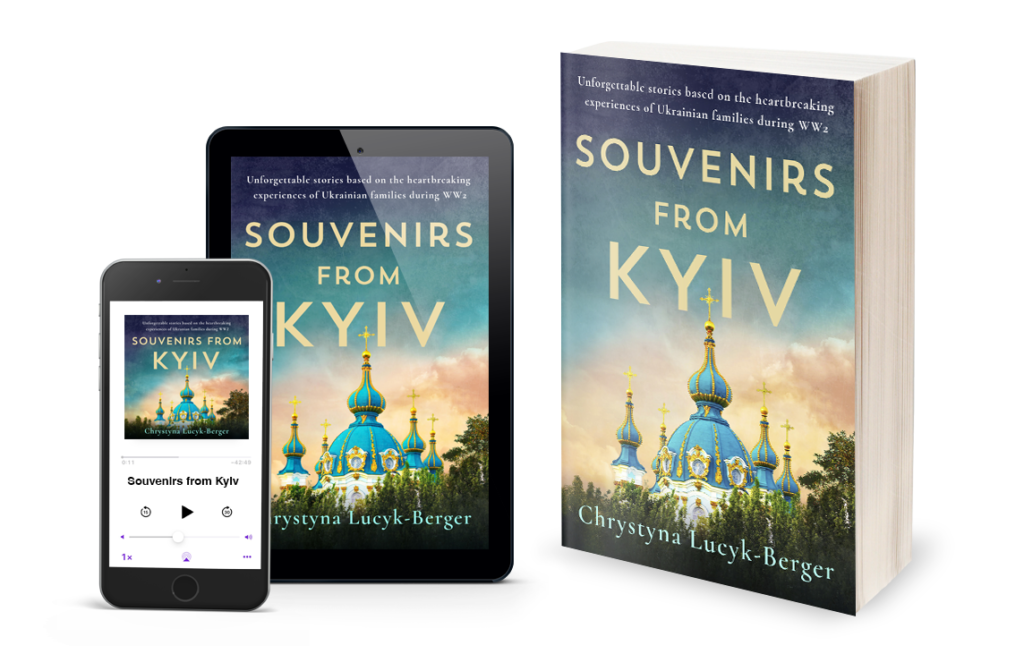

Available now!

Six Voices. Six Stories. One Portrait.

Images from family archive