Click on the button to watch the video in a new window!

(Source: YouTube)

Introduction

Early on in my readings of the Reschen Valley series (which covers the interwar period in Austria and Italy), one of my writing group colleagues observed that my character, Angelo Grimani, notices a lot about what the women are wearing and how people look. I did not hesitate to explain, although I had really given it very little thought. Angelo’s talent for observation was “just happening” as I was writing, and the fact that I immediately understood why surprised even me.

Thanks to research, I was quite aware of how the Fascists influenced the look and feel of “their” new Italian nation. Angelo Grimani, who is an antagonist-cum-protagonist in the family saga, is an Italian war veteran who takes over the Ministry of Civil Engineering from his father-in-law. Angelo’s career, however, is unavoidably influenced by Mussolini’s fascist government, and one thing that the Fascists were keen on was tailoring a careful appearance. This included architecture, sports, automobiles, and fashion. As an engineer, Angelo appreciates good design and function but he also values aesthetics. It is no great surprise then that he quickly learns to appreciate the design behind the “new Italian woman”. Readers will have especially experienced Angelo’s awareness when Signora Gina Conti comes onto the scene in Book 1.

Reining in the Italian Woman after WW1

After WW1, women experienced a milestone in enjoying new liberties. Fashion followed the trends. Skirts became shorter, corsets disappeared, hair was cropped short and women wore makeup. They smoked, drank and drove, creating a new standard of morality. Gina Conti exhibits just this when she invites Angelo to the Laurin Hotel for a midday coffee but they drink martinis instead (Book 2).

The Fascists took up the fashion industry cause as part of their agenda of managing cultural expressions of nation, class and gender in the construction of a New Italy. Once in power, they had to determine exactly what to do with these women, what kind of roles they would have in society and what they should wear while performing their tasks. Their decision was to be reactionary and to drag women back to their traditional positions. This is how Angelo experiences Gina Conti the first time he meets her. She seems to be a willing supporter of the traditional woman but readers learn quite early on that she’s performing. The second time Angelo sees her, she is shopping for flowers and her outfit, for one, reveals that she is not how she seems at the rallies (and Angelo becomes obsessed with finding out what she really is). Then the martini-drinking scene at the Laurin Hotel takes place.

The New Italian Woman was to be the model of femininity as represented by the body-emphasizing cuts of knitted sportswear, and she would accept her place in the patriarchal family, bound up in the hand-tatted lace and embroidered aprons of traditional matronly attire. During this time, emphasis was put on physical fitness and the sports fitness fashion industry was developed with gymnastic and swimwear and other sports-related clothing. In 1939, Mussolini himself organized “The Great Parade of the Female Forces,” a spectacle of feminine Fascist solidarity that was filmed. This will remind anyone, who has read last month’s blog, of the Faith and Beauty Society established by the Nazis.

Fascism took a dim view of the female species and Mussolini declared that they should be “submissive women and strong mothers” like the strong peasant women of the countryside, simple, modestly dressed, and hard-working. Culturally, a policy of ruralization was implemented to encourage Italian women to stay home and make babies for the cause. The fascist state promoted the patriarchal values of the rural housewife by marketing her look, in hopes that women statewide would adopt it. But rarely are women so easily controlled.

Click on the button to watch the video in a new window!

(Source: YouTube)

The Look and Feel of the 1930s Fashion “Fascista”

The ENM (National Fashion Body) tried to forcibly shut off the country from the influence of French haute couture by pushing massaie rurali as the true new Italian woman. Roughly translated, “ladies in the field” represented a tradition of women’s activism that predated the rise of fascism and illustrated the heterogeneity of rural housewives and women workers in the movement. Described as a regional, bucolic style, the massaie rurali look included plain peasant blouses with billowing sleeves, lace-up bodices or square-collared vests, and full skirts. Headscarves or hair pinned back into a braid or low bun allowed women to work in the field or march in the street.

Before Italy became a fashion capital in its own right, it struggled to adapt a national cultural identity in the grips of Mussolini’s fascist regime. What is now recognized as Italian style — glamorous, sophisticated, hyper-feminine — was shaped in part by Mussolini’s attempts to implement this identity. Sleek stilettos, off-the-shoulder necklines, chandelier earrings, and full skirts were adapted from a boho, peasant-style dress, cut and hemmed in neatly with the threads of fascism.

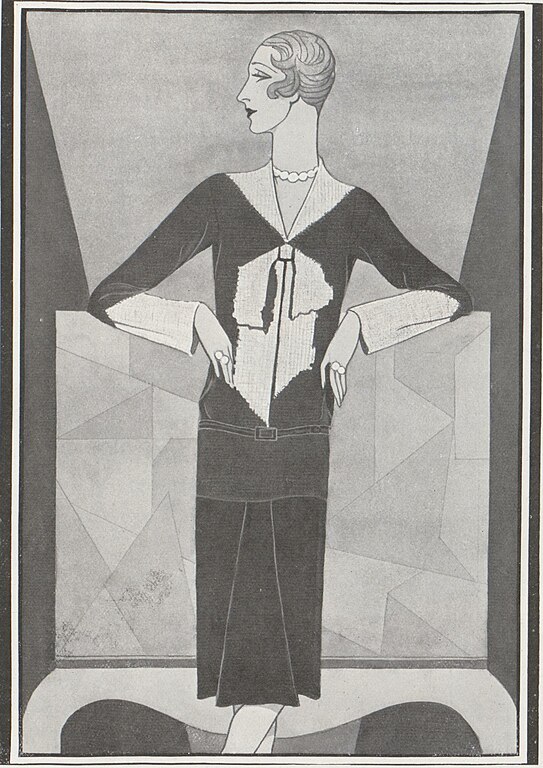

The Italian look, or la dolce vita, is as much conceptual as it is visual. It took its cues from the hard lines of fascism and the idea of the new Italian woman had been co-opted by the National Fascist Party. The styles of the 1930s reflected the hierarchical and military style that swept Europe and wide-shouldered outfits during the day. Suits of slim skirts with militaristic buttons and pockets prevailed over dresses. Dresses were feminine with bucolic overtones and the peasant look and national costumes were strongly encouraged.

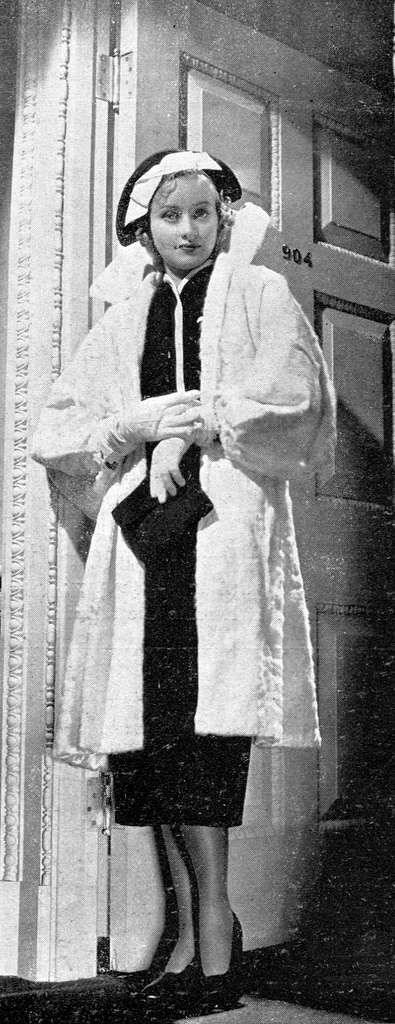

In Bolzano (Book 3), Gina Conti is at a funeral. I used a photo of a suit from 1938 to describe what she was wearing.

Today, Gina was dressed in a black skirt and fitted black blazer that closed with a single large button. The jacket rested just below her rounded hips, accentuating her hourglass figure. Along the hem and up its length, the blazer was embellished by an elaborate white-and-gold scrollwork, which made Gina look as if she were wearing a military uniform. The side cap on her head added to the appearance, whilst the short veil was standard issue for a grieving widow.

Skirts were frequently longer at the back than the front. Pleats and godets were inset into panels from below the knee and these insets gave more fullness at the hemline. The hemlines reached the bottom of the calf within a year. Long and spectacular siren gowns for the evening were cut on the bias. The bias method has often been used to add a flirtatious and elegant quality to clothes.

Elsa Schiaperelli: Against the Grain

Most fashion designers were controlled and required to create fashions that met the criteria of the Fascist dictates of women’s clothing but there were a couple of dissidents that created styles outside of the Mussolini desires. These included the famous shoe stylist, Salvatore Ferragamo and fashion designer Elsa Schiaperelli. Both were highly innovative designers with uniquely quirky minds quite capable of taking the ordinary and twisting it toward a new direction. Both were able to experiment simply because neither formed their fashion sensibilities in Italy. For Schiaperelli, the basic suit was a canvas for inventive trims and embroidery. Women in the thirties with the money to wear her clothes were dressed in very formal fashion and she seldom designed dresses except for evening wear.

Also in Bolzano, I daringly put Angelo Grimani’s mother into a Schiaperelli suit, which is ironic considering she is a stout Fascist supporter. Yet, fashion is her weakness, as we discover in Book 1 when Angelo observes that his mother has fallen for the Parisian-styled cloche. In this particular scene, Maria Grimani comes home to discover Annamarie perusing her books.

Maria Grimani pursed her lips and gave (Annamarie) only the slightest acknowledgment. She was dressed in a beige blazer, the triangular lapels large as sails above her bosom. Beneath the blazer, she wore a fitted black dress, the collar stitched with a twisted bronze design and the hem well below the knee. Just beneath the hem, Annamarie could see the rigid muscles of the woman’s calves, as if they were sculpted to stay permanently tensed. A beige leather purse slung over her forearm hung like a shield. Annamarie saw that the amulet on Signora Grimani’s wrist matched the twisted bronze scroll on the collar. Most remarkable was the grandmother’s hat. Pinned a little off to the side, it looked like a beret with two points, one slightly up, the other flopped down. Annamarie remembered a puppy they’d once had at the farm with one pointed ear and one floppy one, but Signora Grimani was no puppy. No sir. She was a bitch.

Despite the Fascists’ efforts, many Italian women ignored Mussolini’s desire that they dress like peasant women from the farms. Urban women read Parisian fashion magazines, and women of all classes had access to a thriving industry of patterns and sewing machines. When they sat down at these machines, they copied the outfits they saw in magazines, not those costumes worn by the peasant women.

Get the Box Set Season 1: 1920 – 1924

www.xmc.pl Enterprise

November 23, 2020 - 5:17 am ·Resources such as the one you mentioned right here will be incredibly useful to myself! I will publish a hyperlink to this web page on my individual blog. Im certain my site website visitors will come across that fairly beneficial.

Webmaster XMC

January 5, 2021 - 6:52 pm ·Many thanks pertaining to discussing the following wonderful content on your internet site. I discovered it on google. I will check back again once you post extra aricles.

Kongres USA

February 22, 2021 - 9:13 pm ·I am going to go ahead and bookmark this post for my sis for the research project for school. This is a pretty web page by the way. Where did you pick up the theme for this webpage?