After the Great War, in the Austrian province of Tyrol a new conflict began. Imagine you are a German-speaking Tyrolean. You run an inn where, in the summers, Italian tourists come to escape the hot weather. Or you run a large farm, and take on Italian migrant workers to live with you during the busy seasons, and Italian merchants come with necessary supplies of goods like fruit that you would not normally get so high up north. Now imagine that all these acquaintances are told that they can no longer come by because they are at war with you. They cross over some imaginary line on a map, pick up arms, turn around and face off against you. More so, those Italians have no idea that the Russian, British and French authorities have signed a secret treaty stating that, if Italy helps them to win the war, they will be allotted a lot of land that never belonged to Italy in the first place, including where your property is.

And that is how Austria’s Tyrol became a province that had enjoyed a century of autonomy into one that was torn in half, the southern part handed over to the Italians.

My books are riddled with moral dilemmas because that is what I enjoy exploring: normal people in extraordinary circumstances. On my first visit to South Tyrol, when I first saw St. Katharina’s church steeple poking out of the Reschen Lake reservoir, I knew I’d stumbled on a massive David-and-Goliath story. Subsequent trips and research led me to a story filled with political intrigue, corruption and a Fascist design to “Italianize” the German-speaking population once and for all.

During the first years of South Tyrolean integration into Italy, both Italian authorities and South Tyrolean representatives tried to find an appropriate solution for the German-speaking minority. Yet, a movement called the irredenta, or the unredeemed (as in unredeemed territories), insisted that this area should have always belonged to Italy. The leaders of this movement were determined to crush any sense of Tyrolean culture. When Benito Mussolini and his Fascist party took over in 1922, the South Tyroleans faced a different treatment by the Italian authorities. Fascism threatened not only to suppress the language of the German-speaking minority in the north, but also to uproot the cultural identity of that area.

The first and major aim was to Italianize the public language of the area, to Italianize all public inscriptions, town names, street names, and eventually family names and even inscriptions on tombstones. For those who did not comply, they faced major harassment, despotic laws that even regulated their pets and personal belongings. For those who did, they were rewarded with free textbooks, jobs for those who joined the workers’ associations, or who generally collaborated with the Fascists’ economic societies.

And then the government injected the local society with transplanted Italians. “Majoritarianism” was the attempt by the Italian government to generate an Italian majority in South Tyrol. In Bolzano, the government built a new industrial complex and apartment buildings for Italian factory workers. In other cities the government financed the construction of hydroelectric power plants which flooded lands and villages. The government started purchasing land from South Tyrolean bankrupted farmers and provided minor compensation for land destroyed by the flooding. The South Tyroleans had little chance to resist the dictatorial measures.

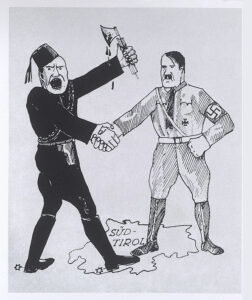

Although open confrontation with the Italian regime was rare, the South Tyroleans managed to withstand most of the Italianization efforts. To counteract Fascist attempts, Germans outside of Italy established a secret relief fund during the economic crisis to prevent further South Tyroleans from having to declare bankruptcy and lose their lands. As Hitler rose to power, so did the South Tyroleans’ hopes that they might have found the leader who would finally bring them back to their rightful place: Austria. Hitler had different intentions. He claimed that Germany’s only possible option was to assure Italy that the South Tyrolean problem did not exist. Despite Hitler’s public renunciation of South Tyrol and despite the development of the German-Italian friendship.

During Hitler’s visit in Rome in May 1938, Mussolini confessed, “The past developments have shown, that this tribe cannot be assimilated.” Therefore he promised that he would make some concessions to the German-speaking minority in the north as long as Hitler guaranteed the pacification of the area. By now, both Germany and Italy were interested in settling this question once and for all.

On June 23, 1939, the two dictatorial regimes decided to move the German-speaking South Tyroleans to German territory in the north and leave South Tyrol with Italy. The two governments gave the South Tyroleans the option either to emigrate to Germany or to remain in South Tyrol and become “good Italians.” At first, the South Tyroleans’ reactions were a fierce rejection of Hitler’s offer to “come home into the Reich.” But soon the Nazi-oriented VKS (Völkisher Kampfring Südtirols, or the South Tyrolean People’s Freedom Party) succeeded in convincing their fellow countrymen that the South Tyroleans’ resettlement in Germany was a necessary “sacrifice.”

The propaganda that evolved on both sides during the months following the June discussions, eventually divided the German-speaking South Tyroleans population into two hostile camps, those remaining and those who opted for Germany.

Almost ninety percent of the population opted for emigration. Those who voted to stay were condemned as traitors while those who chose to leave were defamed as Nazis. The Option destroyed many families and the development of the economy of the province was set back for many years. The first families left their homeland in 1939, and by 1943 a total of around 75,000 South Tyroleans had emigrated, of which approximately 50,000 returned after the war.

The era of the Option, however, had opened a deep gap among the German speaking population of South Tyrol. Those remaining were in the minority and were repeatedly exposed to persecution by those who had opted to migrate. They were treated like betrayers of their country, their nationality, their blood, and their homeland. The hatred between the two groups did not know any confines. Children left their parents, neighbors burned their neighbors’ houses, priests fought each other from the pulpit. In 1943, when Hitler’s troops finally marched into the South Tyrol, the situation of those who had opted to remain became even worse.

Seventy-three years after having their autonomy stolen from them, the German-speaking minority in the north of Italy succeeded in securing the ethnic, cultural, social, economic, and political uniqueness of their homeland. And that is where the next book, following Annamarie’s story further, will take me.

For more information on the Option, see:

Eva Pfanzelter, The South Tyrol and the Principle of Self Determination: An Analysis of a Minority Problem

Get the Box Set Season 1: 1920 – 1924