Just before Christmas, 2019. My girlfriends and I are sharing cake and nuts, olives and cheese, and a lot of wine, and somehow the conversation turns into something that sends us into peals of laughter. The kind of laughter girls—even over 50—have when they’re talking about subjects that may be otherwise inappropriate in any other company.

And then one of the women in our group says, “Well, I have a story.”

By the time she is done telling us, my mouth is on the floor and the first words I manage are, “Can I please have that story? Can I, like literally, possess it? Because I want to write it. I want to know who would go to such great lengths for what I can only see as an act of revenge.”

Featured image: Terezín Concentration Camp / by Ursula Hechenberger-Schwärzler

My friend’s story had to do with her husband’s birth in Moravia, a district of the then-Nazi occupied Sudetenland. Her father-in-law was, during the occupation, a commanding German officer—a Nazi. Her mother-in-law was a woman who believed she was entitled to rule over the Slavs in the district. Her reputation proceeded her; the entire town detested her. She was also expecting a child, and when it was time, she summoned a midwife. When the boy was returned to the parents, it was not until all the staff had departed the house that they discovered the baby boy had been circumcised. The man who eventually married my friend never received an accurate explanation. “You were born that way,” was his mother’s answer.

Now for an American, like myself, circumcising your son is not unusual in the least. That was our great debate that evening around the wine and snacks. But in Nazi-occupied territory, in 1942? Not quite the mark you want found on your personage, and if your father has aspirations for you to serve the Führer? Just going to musters would have put the boy’s life in danger!

Like I said, I was aghast. And intrigued. I wanted to dive into the mind of the person who conducted that most sacred ritual. I wanted to know what they were thinking and what had driven them to do it. I knew I had a story. And I had a short story, ending on that very decision; ending just before the very act. “L’chaim,” my protagonist cries. For life! An act of vengeance? Or an act of defiance?

Regardless how short a story is, or how long a novel is, if you’re reading and writing historical fiction, the author has gone through great lengths to do a lot of research. I stayed true to my friend’s anecdote and placed the characters in the Sudetenland, which meant discovering a whole new territory. So, here’s a peek into my historical summary. It’s a timeframe of the events leading up to the German occupation of the Sudetenland.

The Sudetenland

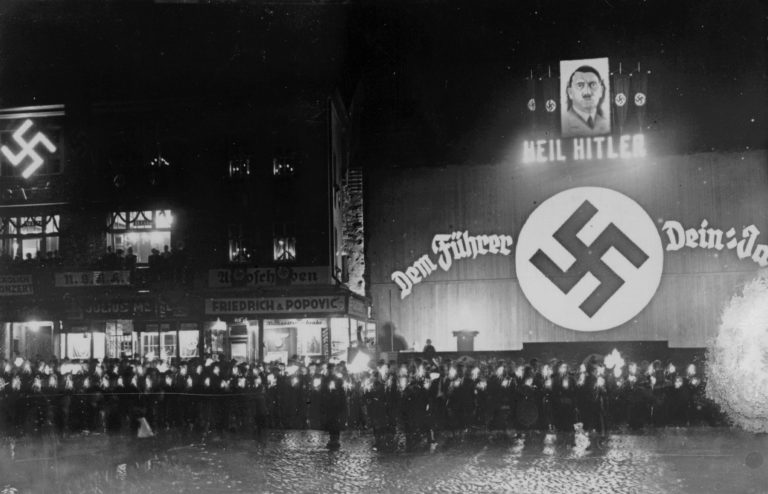

When Germany and Austria-Hungary lost the first world war, territories containing a population of Czechs, Slovaks, Poles, Hungarians and 3.5 million Sudeten-Germans were granted to Czechoslovakia. When the Nazis won enough power in Germany in 1933, they began a policy of autonomy and segregation. Some four years later, Hitler revealed his plans of annexing Austria and Czechoslovakia to the leadership of the Wehrmacht, or the German military. The public first learned of his ambitions in a speech Hitler made in parliament stating that he would enforce the right of the Germans abroad to self-determination. In other words, he was making a demand for annexation. A month later, he did exactly that with Austria.

The Nazi government’s next step was to demand autonomy and reparations for Sudeten Germans. Other minorities in Czechoslovakia decided it was a good time to make their own demands. At the time, it was President Benes who headed the Czechoslovakian government, and he rejected Germany’s demands. In May 1938, Czechoslovakia mobilized its forces. When Göring suggested that Poland and Hungary try to wrest territory back for themselves, both countries placed their demands as well. The snowball began tumbling down the slope. By August that same year, 750,000 German troops moved to the border, claiming they were only there for maneuvers. In September, Hitler once more gave a speech in parliament and announced that he would “not tolerate the suppression of the national comrades in Czechoslovakia”, meaning the Sudeten-Germans. Riots broke out in the Sudetenland.

England sent Chamberlain to the rescue, and he spoke with Hitler but it was too late. By September, it was a done deal. Not a week after Chamberlain’s meeting, Czechoslovakia accepted an Anglo-French plan to segregate the Sudetenland. Three days later, Hitler made it clear to all involved that he rejected Chamberlain’s suggestion to annex the Sudetenland and demanded the division of the entire Czechoslovakia. This sent the Czechoslovakian forces into a general mobilization. By the end of the month, France mobilized her armies and between September 29 and 30, Daladier of France, Chamberlain of England, Mussolini of Italy, and Hitler signed the Munich Agreement, which allowed Germany the annexation of the Sudetenland. On October 1, the Wehrmacht marched in. One month later, under the Slovak People’s Party, Slovakia declared itself independent and became an ally to Nazi Germany. The countries were torn asunder by Nazi collaborators and Nazi dissidents.

And that is the historical framework for The Girl from the Mountains née Magda’s Mark.

AN EXTRACT FROM

The Girl From the Mountains

From Chapter 1

When the German motorcade rolled past Voštiny opposite the Elbe River, Magda and her mother were singing “Meadows Green” and threshing the wheat. Their song dissipated like smoke into the air. Magda’s mother straightened, one hand on her headscarf, like a gesture of disbelief. No tanks. No marching soldiers. Only those gray-green trucks and black automobiles on the horizon.

The procession moved on south, growing smaller in size but larger in meaning. When she looked toward the fields, Magda saw her father and her two brothers also pausing, one at a time, to witness the Germans chalking off the Sudetenland demarcation with their exhaust fumes. The Nováks’ farm lay within it.

Magda’s father faced the cottage and an entire exchange silently took place between her parents.

Then the rumors are true, her father said with just the simple lift of his head.

Her mother pursed her lips. What now?

Magda’s father sliced the sickle through the stalks. We finish the wheat.

And with that, Magda, her two brothers, and her parents went back to work.

Later, at midday, urgent knocking rattled their door. Everyone in the house froze except Magda. She turned slowly around in the room, as if this was to be the last scene she would remember. Her father held the edge of the table. Her mother rose from her chair. She was straight and proud and beautiful with an open face, the kindest light-brown eyes, and full lips. Magda’s brothers, Bohdan and Matěj, sat rigid in their chairs. Each of their wives held a child. And Magda’s grandparents sat so close to each other on the bench against the oven that they might as well have been in each other’s laps.

The knocking came more insistently, and this time they stirred into action. Magda’s father pushed himself from the table and left the room. The rest were in various stages of attempting to look normal. A moment later, her father returned with the village heads. With baffling lightness, he offered them Becherovka as if it were Christmas, and shared a joke about a cow and a farmer—Magda was not paying attention to the story or the punchline that then made them laugh so.

The Sudetenland, the village wise men announced after the first schnapps, was now part of the Third Reich. Hitler was protecting his people. And that was why no other country called foul for breaching the treaty.

“But we will not go to war,” one village elder said, “as we may have feared.”

“Imagine that,” Magda’s father said abruptly. It was the tone he used when angry.

Her brothers, however, visibly relaxed.

Pat

November 21, 2020 - 2:28 am ·This really sounds like a book worth reading! I have read a lot about WW2 and look forward to reading this.

Chrystyna

November 21, 2020 - 7:12 am ·Thank you, Pat! Delighted to have your interest! All the best, Chrystyna

Ursula

November 27, 2020 - 2:21 pm ·Dear Pat,

“The Girl from the Mountains” is now available for pre-order from Amazon, Apple, Kobo and Google. Here are the links:

Amazon: https://bit.ly/37cgwWe

Apple: https://apple.co/3fA6oua

Kobo: https://bit.ly/3q34hnx

Google: https://bit.ly/39goIrh

I hope you’ll enjoy reading this story.

All the best, Ursula