In recent weeks, many of my readers have sent me links to various articles about how the remnants beneath the Reschen Lake Reservoir have “come back to the surface” (https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-57156312). The thing is, it happens every time the reservoir is drained but because of a Netflix series called Curon (an Italian production and referring to the Italian name for the village of Graun), the Reschen Lake Reservoir has been enjoying renewed interest.

The headlines claim that lost villages are found. The villages were never lost as in misplaced. Livelihoods were lost. The homes were detonated. The stairs were not lost, the concrete foundations were not lost, the artifacts of a centuries-old lifestyle were not lost. They were destroyed. Livelihoods and entire families were torn apart—wounds so deep that over 70 years later, they are at times still raw and festering. In this month’s blog, I share some of the stories beneath the surface of the place that inspired The Reschen Valley Series.

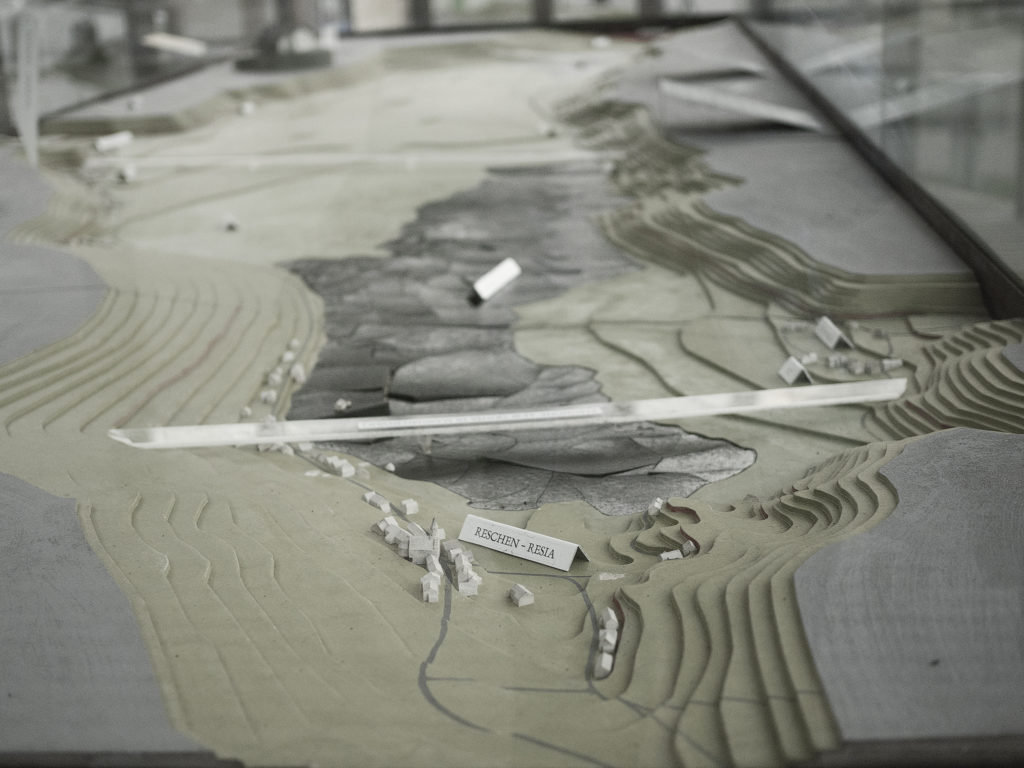

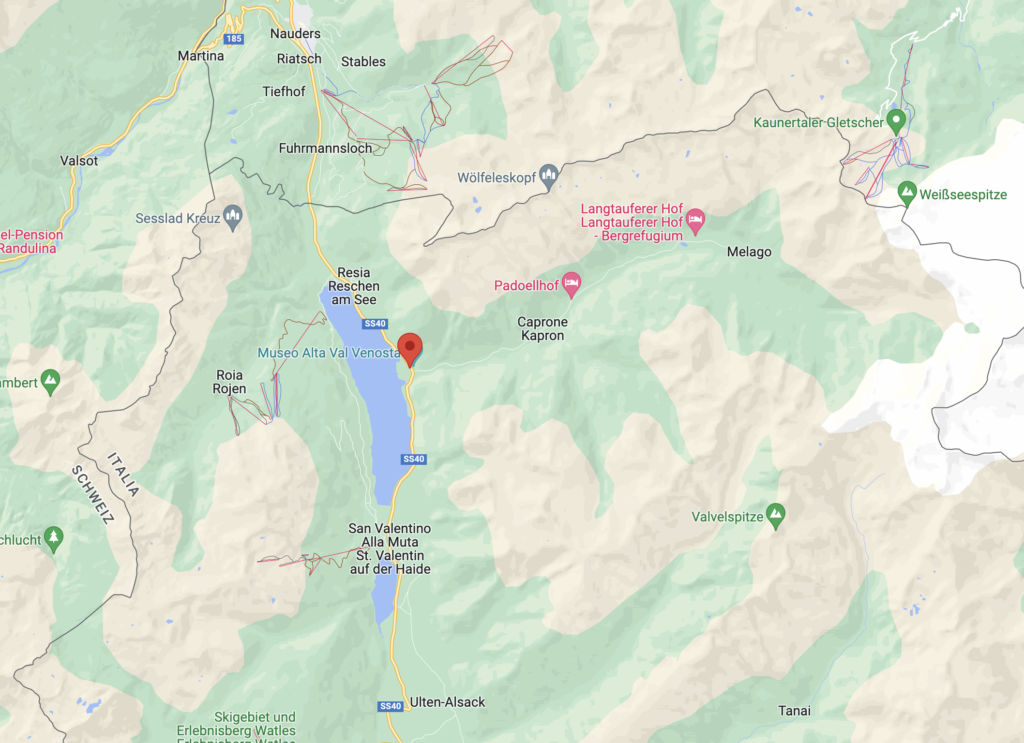

Five kilometers south of the Reschen Pass on the Austro-Italian border, you will come to Graun in the Vinschgau Valley. A 15th-century church tower rises out of the water. Six kilometers long (about 4 miles), the reservoir contains a volume of 116 million cubic meters and generates 250 million kWh of electricity per year. Today, this lake on the northern Italian border serves as a massive tourist destination and a visual testament to a conflict between the German-speaking population and Fascism.

In the Name of Progress, and a Means to Subdue the Population

Between 1949 and 1950, the villages of Graun and Reschen in the Upper Vinschgau Valley became victims of a reckless dam project. If you read the Reschen Valley series, you will get a pretty accurate account of the awful corruption and backhanding that went on before five hamlets and 2 towns fell victim to the flooding.

The intentions were relatively honorable at the start. Italy aimed to catch up with American industrial standards to fill their coffers with war machines. Italy had suffered major disasters in WW1. They might have been on the winning side, but as one historian put it, Italy was so unprepared and so badly equipped, it was like sending their soldiers out to fight with their pants dropped down around their ankles.

The embarrassments did not end there. The Treaty of Versailles left Europe with the bad feeling that a second war would break out soon and it began preparing itself.

The citizens of the new “South“ Tyrol – the province where the Reschen Lake Reservoir is located – was one of those groups who were up in arms about the treaty’s final results. Austrian Tyrol had been severed in two and the south was simply handed over to Italy thanks to a 1915 secret treaty signed by France, Russia, GB and Italy. That treaty stated that, if Italy helped the others to win the war against Germany, they could get their coveted mountain borders at the Brenner Line.

Plans for a dam that would connect the lakes of Reschen and Graun (or Middle Lake), had gone back as far as the beginning of the 20th century. However, after the project was assessed by geologists, it became clear that the man-made construction would ruin too many livelihoods, and there were laws that protected the citizens from that.

The Italians knew of these laws, so in 1920, when the annexation of South Tyrol to Italy was official, they were deemed no longer in effect and planning went full steam ahead. Except tragedy struck: a dam break to the north killed over 300 people in 1924. The government put a halt on all projects until new safety measures were put into place. Italy had been using cheap materials left over from the war and there was also an enormous amount of corruption in the various departments responsible for building roads, dams and bridges. Because the state needed money, they sold some of these projects to private interests and supposed cooperatives made up of groups of industrialists looking to monopolize the “white gold” resources (referring to the abundance of lakes, rivers and streams in South Tyrol).

The German-speaking residents of South Tyrol, meanwhile, were suffering under a pogrom of oppression under the Italian nationalists, those that would soon come into power under Benito Mussolini. Because of the forecasted war to come, the Italian King was persuaded to decree a large number of projects, come what may.

A documentary by Georg Lembergh and Hansjörg Stecher can be seen with English subtitles on Apple TV!

Click on the button to watch the trailer on Youtube.

The Heart of the Vinschgau Valley

The towns of Reschen and Graun were built on medieval foundations that were kept up and well maintained. Some of the homes retained the original architecture, too. Oriels hung out over the streets, most homes had two or three levels with beautiful stairways. Box windows and sills were illustrated with decoration and displayed beautiful flowers. Painted onto the houses were usually the family’s trade or family crests. There were 163 houses between Graun and Reschen (within walking distance of one another) and 523 hectares of fertile cultivated land. By the time the valley was flooded, more than half of the 650 inhabitants of Graun had to move away, and all together about 1000 people were affected by the catastrophe. 120 farms were lost, which was almost exclusively linked to cattle breeding.

As I indicated, the Austrian monarchy had already proposed a reservoir that would connect the Reschen and Graun lakes by raising Graun lake by about 5 meters. The extent of this damming would not have been very alarming, since it would not have endangered the villages of Graun and Reschen. Later, however, the Montecatini group (now Edison) took over this concession and worked out a new, far more dangerous project. In the series, the names of these enterprises are Grimani Electrical and Monte Fulmini Electrical (MFE).

Six days after Hitler and Mussolini signed the Option agreement (June 29, 1939), the company presented its new project, which foresaw the damming of the lakes from 1,475 to 1,497 meters, i.e. by 22 meters, which would result in the destruction of all of Graun and a large part of Reschen.

The plan was published by the fascist municipal secretary in Graun. The announcement was in Italian (German was forbidden) and was hung among many other decrees. Legally, it should have hung there for two weeks, so that the affected citizens could raise objections if they had any. But because it was practically hidden amongst the other notices, nobody took note of it. Furthermore, after only eight days, the secretary reported no objections . Although this procedure was completely illegal even in Fascist Italy, the Roman Ministry gave Montecatini authority to begin construction, at the same time declaring the work urgent and not to be postponed. But the events of the war put a stop to this and after the occupation of northern Italy by the German Wehrmacht in 1943, the work was completely suspended.

The residents of the valley believed the issue was moot, although the ground around the lakes had already been indelibly changed by the initial construction. After the war, Italy was in the hands of a new democracy, and the hope was that the project would be forgotten. However, to the consternation of the affected population, on March 20, 1947, two representatives of the Montecatini Company appeared in Graun and announced that the work for the realization of the dam project would be resumed and completed by 1949.

Many attempts were now made to avert this impending disaster. They all failed.

In addition, Montecatini was threatened with legal proceedings because the population had claimed the procedures in which the proposal was made was illegal and that the plans to raise the lake by 22 m instead of 5 m would have required a new concession. This threat made the company really nervous, because it saw its project in danger. Therefore, the chief engineer came up with the counter-threat that if the project was revoked, the company would demand compensation from the state for the high expenses already incurred. The government countered that by making great promises to the inhabitants of the valley. Empty promises. Regardless, Montecatini and the State were facing great financial hardships.

How Switzerland „Rescued“ the Project

An electric power plant was to be built in Rheinwald, Switzerland, which would have flooded the village of Splügen and part of Mendels. However, the people of Rheinwald resisted and the Federal Council did not grant a concession. The Swiss company Elektro-Watt then approached the Montecatini Group about participating in the Reschen reservoir.

Elektro-Watt offered Montecatini 30 million Swiss francs as a loan; in return, Montecatini had to supply 120 million kWh of winter energy to Switzerland for ten years. It was the Swiss Association for Home Security that uncovered the loans an reported the whole scandal in 1949 in the association’s magazine. There were a lot of angry people, and the Swiss were deeply shamed.

Unfortunately it was too late and the course of events could not be stopped. And for the delegation from Graun, which went to Zurich to meet the governor of Tyrol, Elektro-Watt also delivered only empty promises.

Resettlement

Montecatini built a city of barracks as temporary housing for the residents of the valley. In all this time, the Tyroleans were still waiting for their final offers on their homes, the initial offers having been ridiculously undervalued during Fascism. The people who were forced to resettle were not given a plot of land but simply offered money. And as far as the money was concerned, the amounts offered for the expropriated fields did not correspond in any shape or form to their real values. Requests for Prime Minister DeGaspari to intervene brought nothing. The South Tyroleans begged their priest, Alfred Rieper, and the Bishop to go to the Pope. There were a lot of sympathetic sentiments exchanged but nothing concrete to save the valley.

An Impressive Cattle Show

In order not to have to pay appropriate compensation to the land owners, Montecatini stubbornly held on to the opinion that the Upper Vinschgau Valley was a low-yield and barren area, in which it was not worth living.

The South Tyrolean deputies elected in the first parliamentary elections in 1948 invited the Minister of Agriculture and later President of the Republic, Antonio Segni. He arrived in Graun to a unique and impressive cattle show on the valley’s floor. In his book Mit Südtirol am Scheideweg (At the Crossroads with South Tyrol), Friedl Volgger described Segni staring at the scene before him. The whole plain—the entire stretch that is the Reschen Lake Reservoir today—was teeming with cattle and livestock. Literally, as far as the eye could see, nothing but cattle, cattle and more cattle.

The prime minister had tears in his eyes. He could not prevent this development, but he would see to it that the farmers were at least properly compensated. Segni gave the Montecatini lords a proper “status briefing; an agreement was reached between the Montecatini and the representatives of the population. A joint commission had to re-evaluate old properties.

Recent interest in the lake drummed up by the Netflix series, Curon (an Italian production), the Reschen Lake Reservoir has been enjoying renewed interest.

Click on the button to watch the trailer on Youtube.

The Farmer’s Uprising

But the tragedies were far from over. The final settlements were to be made in April 1949, but nothing came. The government and Montecatini, however assured the farmers that they would have time to bring in the harvest. On August 1, 1949, the farmers awoke in the morning to water seeping up and into their fields.

Without warning, the sluices at the dam had been closed on a trial basis and the water was going to ruin the entire harvest. The local citizens had had enough. The bells of St. Katharina rang the alarm for a storm though the sky was blue. Armed with sticks, pitchforks, sickles and rage, the men marched to the town of Reschen to the offices of Montecatini and called the lords down.

But the company’s officers had obviously already been informed of the danger. They tried to steal away in their cars but the mob, led by the priest Alfred Rieper, intercepted them and forced them to drive back to Reschen for the confrontation. The Italian government intervened and called in the police. Father Rieper, and two other men were arrested. The final offers on the lands arrived in October.

In the early autumn of 1949, everyone was confronted with the difficult decision to emigrate within Italy or even leave Italy, or to resettle on the slopes of St. Anna above Graun. About 30 of the 120 parties decided to stay in Graun and commissioned the architect Erich Pattis with the planning of a new settlement. For many families, however, there was no more room in Graun and Reschen. They had to leave the land of their forebearers, wandering all over South Tyrol and Italy in search of a new home.

In Graun and Reschen, Montecatini began to set off the explosives and leveling the houses and buildings, parish churches and old cultural assets. An eyewitness wrote about it: “Graun is in its last throes. Like a terminally ill person, limb after limb is being cut off. Day after day the water advances, day after day the blasts resound, and as soon as the smoke has cleared, another house collapses within itself.”

And then it was time to level the church in Graun, St. Katharina. Those who read the series will wonder whether I chose Katharina Steinhauser’s name to represent the church. I will tell you about one of the many strange coincidences I experienced in writing these books: I had no idea that the church was named after St. Katharina until I was nearly finished with the first book.

“Sunday, July 9, 1950, the last service. Instead of the side altars, the emptiness of the plastered wall yawned. The organ had already been removed. Heartrending were the farewell words of the pastor from the pulpit. Many people wept. In the afternoon the Blessed Sacrament was transferred to St. Anne’s little church on the hill above the dying hamlet. Sunday, July 16, 8 o’clock in the evening, the bells rang for the last time to bid farewell to their old Graun. Together they rang for half an hour, and then the big one for five minutes. On July 18, the big bell was removed from its tower, which it had occupied since 1926. The next day it was followed by the old bell (from 1505), which had rung in all the sorrows and joys of the valley for centuries. At the same time, the covering of the church roof and the demolition began.”

On July 23, 1950 (on a Sunday) the first attempt to demolish the church was made. The villagers’ hearts broke. One describes it as watching someone slowly die. It took several attempts, and though the church collapsed, the tower did not. Over and over, Montecatini tried to detonate the tower. Over and over, it resisted, and the villagers swarmed down to beg the company to leave it. In a final effort to save something of their valley, they eventually won and the tower was allowed to stay up, like a tombstone.

Further reading Tip

For even more information, some interesting video footage and stunning images. The article and interviews are in German but if you are really interested try Google Translate!

Information and anecdotes gleaned from the History of Old Graun, edited by Ludwig Schöpf and Alfred Plangger from the original German.

http://www.reschensee.it/index_htm_files/Geschichte-Alt-Graun-04-2015-1.pdf

Photos by Ursula Hechenberger-Schwärzler

Get the whole series

Trisha Faye

May 30, 2021 - 5:53 pm ·Excellent, excellent post! I had tears in my eyes as I read the history of what happened here. I am so glad that so many years later, you are able to pay tribute to the people and the lands here. Although it can’t reverse what happened, or bring anything back, at least the memories and lives can be honored by your books and your posts about it.