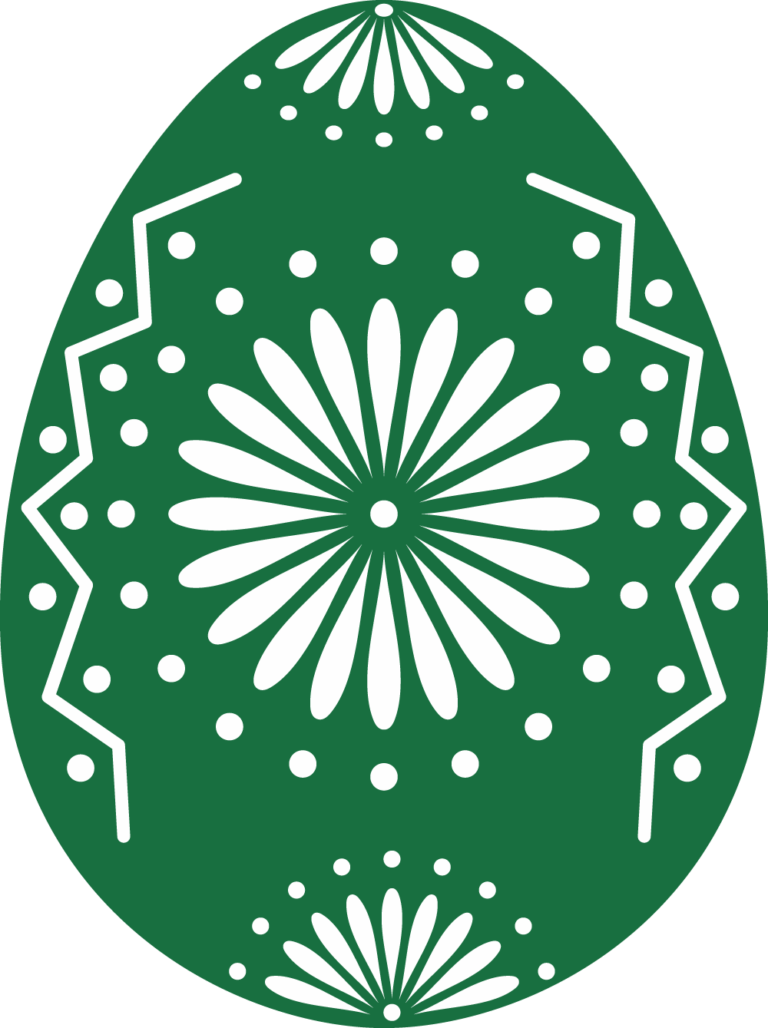

Easter is my favorite holiday, and with a Ukrainian Orthodox mother and a Ukrainian Catholic father, our family celebrated it twice a year, save for when Easter landed on the same Sunday around every four years. My brother and I called that the “Marathon Easter” weekend. We started the holiday off by going to church at 11 p.m. on Saturday at St. Michael’s (my mother’s). Church ended at around 2 a.m. (it sounds grueling, but it is truly one of the most beautiful rites ever, with a candlelight procession and dramatic opening of the “tomb” by the priest!). After the service, we all piled into the big church hall to bless our baskets. The baskets contained paska, babka, sausages (we hadn’t eaten meat all week so that was torture, that garlic!), salt, butter and the famous Ukrainian pysanky: beautifully, hand-painted eggs that were the pride and joy of every Ukrainian family.

These eggs are so treasured by every Ukrainian family that my mother had even purchased a massive coffee table with see-through glass and a deep drawer so that she could exhibit her collection year-round.

Once, and only once, we had to vacate the house because some of our pysanky exploded from the hot sun. Unlike the Russian eggs, which are hollowed out, Ukrainian eggs remain whole, the yolk and egg white eventually drying up and creating a kind of tiny rattle. But if you’ve just purchased freshly made ones, and they explode… The only kind of mask that will help you here is a gas mask.

The pysanka (PYH-san-ka) is decorated with traditional designs using a wax-resist (batik) method. It dates to the pre-Christian era. In excavations of the earliest Trypillian site from the 5th to 3rd millennium BC, archeologists discovered eggs made of pottery with stones inside to create rattles. They bore decorations meant to scare evil spirits away.

Throughout the world, the egg represents the rebirth of the earth and was believed to have special powers. As in many ancient cultures, Ukrainians worshipped a sun god, Dazhboh, as the sun is a source of life. Eggs decorated with symbols from the natural world became an integral part of spring rituals and served as beloved talismans.

Many superstitions were attached to the pysanky. Spiral motifs were most powerful because demons could be trapped in the spirals. Broken pysanky had to be disposed of by grounding shells or breaking them and throwing them in water so witches couldn’t use them for evil.

Creating Pysanky: The Unbelievable Art Behind Ukrainian Easter Eggs

The Hutsuls (people living in the Carpathian Mountains in southwestern Ukraine) believed that the fate of the world depended upon the pysanka. If the custom continues, the world will as well. If this custom is abandoned, evil – in the shape of a horrible serpent who is forever chained to a cliff – will overrun the world. Each year the serpent sends out his minions to see how many pysanky were created. If the number is low, the serpent’s chains are loosened, and he is free to wander the earth causing havoc and destruction. If the number of pysanky increases, the chains are tightened and good triumphs over evil for yet another year.

With the advent of Christianity in 988, because of the popularity of the pysanka, the symbolism of the egg was changed to represent not only nature’s rebirth, but the rebirth of man. Christians embraced the egg symbol and likened it to Christ’s Resurrection.

Pysanky were traditionally made the last week of Lent. The women of the family gathered at night after the children were asleep, said the appropriate prayers and went to work. Some of the patterns and decorations became carefully guarded secrets – a sort of herald for the family – and were passed down from mother to daughter.

Each region of Ukraine also developed their own styles and usage of color. Dyes were prepared from dried plants, roots, bark, berries, and insects. A stylus, or kistka, was prepared by winding a piece of thin brass around the needle and a hollow cone. This was then attached to a small stick with more wire.

Kistkas from traditional to contemporary

The women heat the beeswax and dip their styluses into it. The molten wax is then written onto the raw white egg and any bit of shell covered with wax is sealed and remains white. The dye sequence is always light to dark. So all the parts of the egg that should remain white are covered first. Then, the egg is dyed in yellow. All the parts that are to remain yellow are then covered with the wax and then comes orange or green, then blue, and so on. After the final color, the wax is removed by gently heating the eggs in the stove or up against a candle flame. Then, we gently wipe off the melted wax to reveal the entire design and pattern.

To give someone a pysanka is to give a symbolic gift of life. Everyone, from the youngest to the oldest receive a pysanka for Easter. The designs and colors on the traditional folk pysankas have a deep symbolic meaning. A bowl of pysanky was kept in every home, not only as a colorful display but also as protection from all dangers.

During Communism, the art of the pysanka was forbidden in Ukraine. The Ukrainian diaspora, however, around the world, maintained the tradition. My home city of Minneapolis, Minnesota became the pysanka capital of the world. My aunt made beautiful ones, and I remember we used to have pysanka parties when she still lived in Minneapolis. I still remember one of my first ones. It was awful compared to the exceptionally detailed, intricate and straight (!) lines others were able to achieve.

When Ukraine was once more independent, the art was reborn, but now there are many contemporary designs and modern dyes and kistkas that help make things easier. You can even buy an entire kit and try for yourself. But please… be careful of the heat. Seriously, you don’t want to have to vacate your home.

Image source: by http://artalbum.org.ua/ru/site/license – http://artalbum.org.ua/, Public Domain

Sources: Lesya Lucyk

Source featured image: By Lubap Creator:Luba Petrusha – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=15048048