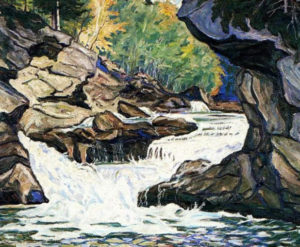

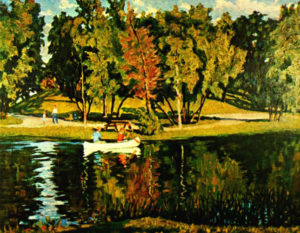

I grew up surrounded by beauty. In the upper duplex apartment in Northeast Minneapolis (USA), almost every inch of wall space was covered with oil, pastel and watercolor paintings. Some my father’s, many my grandfather’s. Over the entertainment system, where my father played classical music—from Amadeus to Abba, from Chopin to Donna Summers—hung the painting of Castle Neubeuern, where my father and his family spent the first years of post-WW2 in a Displaced Persons (DP) camp. Next was a painting of the Königssee in Bavaria, dated 1946. My father’s landscapes of the Mississippi River and Lake Pepin. were after that. There was also a photograph of the grandfather I’d never met: a handsome man with classical, “old world” features. But it was those landscape paintings that inspired me for 16 years. Meadows, lakes, the Alps, still lifes of flowers in folkloric vases that were not American in any way.

Is it any wonder then, that when I landed in the Alps in the summer of 2000, I felt like I had come home? Only as I was writing The Woman at the Gates, did I start making all of these connections. I set out to write a story about my family’s journey, only to come to understand my very own.

Moving to Austria on an impulse is something I still marvel about. I was standing on a mountain, overlooking a valley when I made the decision to quit my job as a managing editor, had my parents sell my car, and tossed my airplane ticket to have no pressure in figuring out how I would make a living in Austria. After all, I believed I’d landed in paradise. And I was not wrong. Making that decision was also the first step in a long journey of self-discovery.

I know my grandfather only through his art and oral history. My father and his family arrived to the U.S. from Germany back in the Fifties as Ukrainian refugees. My father remembered Ukraine. My mother, on the other hand, was born in Salzburg in 1946, in a DP camp to her Ukrainian refugee parents. My parents met in the Ukrainian diaspora in Minneapolis—a thriving community made up of people from the “old country” who were active during the Cold War, convinced they could persuade the international community to rip Ukraine out of Stalin’s grips.

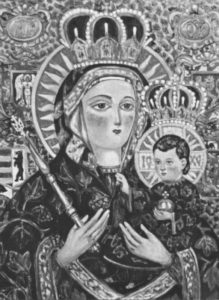

In the meantime, marriages were formed. Children were born—grandchildren. We first-gen Americans grew up bilingual, preparing for the day that we would all return to “the homeland”. On Saturdays, we attended Ukrainian school, went to Ukrainian churches, joined Ukrainian organizations. Those organizations were our first introduction to politics… And we were told where we’d come from. Who our relatives were that had been left behind. And what the ones in the U.S. and Canada had had to do to get to the United States. All of them had essentially started from scratch with two dollars in their pockets, which is what they got when they landed on American shores. My grandfather—a renowned artist, who’d studied post-impressionist art in Paris—never returned to his standing. He died at the age of 57, on the same day he’d been born.

Stepan Lucyk was born in L’viv, Ukraine in 1906. After graduating from “high school” he went to study art with Olexa Nowakowski, a renowned artist and teacher. A natural and genial leader, Stepan Lucyk was soon recognized at the private school and, together with other students, insisted on and found teachers who introduced different artistic techniques, such as perspective, chemical composition of paints, and tempura for frescoes in churches. Learning those techniques helped save his family’s lives in 1944.

But before the war, Stepan already had quite a reputation and renown. In 1931, he was invited to study in Paris. At that time, the French capital was the center of new artistic ideas and a large artistic colony. Post-Impressionist artists like Picasso, Matisse, Maurice Denis, and others were taking in students. He interned with one of the artists, whose simplicity in studying forms and composition influenced Stepan in all his drawings. However, his favorite artists were the impressionists such Monet, Manet, Renoir, etc. and he mainly painted with their techniques.

He stayed in Paris for about six months before returning to L’viv. He and his fellow students made excursions to the Carpathian Mountains, where Stepan fell in love with the Hutsul culture and the mountains. Many of his motifs reflected his love of nature and the Hutsul folklore and traditions. During one of their excursions, he met his wife Ol’ha, who was visiting her sister in Kosmach. In a memorial book published about him, she described how they met in church, how he and his colleagues were later painting the villagers and, that evening, there was a village dance. He walked my grandmother home on that romantic night and serenaded her. She, in the meantime, had a career as a concert violinist and wrote poetry, stories, plays and music. In The Woman at the Gates, my grandparents are depicted in the characters of Roman and Lena Mazur.

The Second World War

Both my grandparents were very well known for their arts. They had a huge network of emigres outside of Ukraine thanks to Stepan’s travels and it was this network that saved their lives on more than one occasion. As a matter of fact, essentially everything that takes place from Slovakia to Bavaria in the novel is based on my father’s and uncle’s recollections.

In 1943, with plans to sit out the war in Switzerland, the Lucyk family, with their sons Yurko (my father) and Roman (my uncle), escaped over the border. Antonina Remenet’ska, my grandmother’s sister, also went with them. She’d worked as an operative in western Ukraine, and from a remote mountain village in the Carpathians, effectively helped Ukrainians flee into various western diasporas over the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists. She was with the Lucyks from the moment the family crossed over the border to the end of the war. She is The Woman at the Gates.

One of their first stops was in a village in the Slovakian Tatra Mountains. They were supposed to move on shortly after. However, battles were raging and the remote village actually provided a sort of comfortable cover. When the locals discovered my grandfather’s artistic talents, they hired him to renovate the frescoes in a chapel. Payment came as food, and my father recalled my grandfather returning with a wagon full of hams, beans, potatoes, vegetables and fruit that he shared with their host families and their neighbors.

The whole family was staying in that village in Slovakia when the Gestapo suddenly appeared, surrounded them and deported everyone they found. While doing research, I was asking myself why that village, at that time, and why these people. It was as I was writing The Girl from the Mountains that I had learned about the Czech and Slovakian uprising. It was around that time that my family was arrested and sent to a labor camp outside of Berlin. In The Woman at the Gates, I built that uprising in as the reason for German reprisals.

The labor camp at Wilhelmshagen was a nightmare not only for the reasons that any concentration camp in those days were, but because Stepan grew desperate, enough to risk his life and face off with the camp Kommandant. Antonina was experiencing something so awful, she had stopped speaking. Ol’ha was losing her hair from the stress. And their young sons were starving to death. Yurko – my father – was literally on his last legs, his stomach swollen, which is one of the last stages before death.

Through Stepan’s ingenuity and his paintings, he managed to convince the Kommandant to release them so that they could take Yurko in to see a specialist. During one of the trips, he was able to contact an artist friend in Berlin, and they escaped from the camp and ended up in Bavaria. Subsequent blogs will reveal more details about those events.

The war, in the meantime, was approaching its final climax. The family was also coming to terms that, if the Soviets regained control over Ukraine, there was no way back. They would be arrested and sent to Soviet reeducation camps as soon as they stepped foot back over the border. And that was the least scary of their possible fates. To help prevent repatriation, Antonina helped secure fake Polish identifications.

The Chiemsee Artists

Right after the war, many Ukrainians washed up in the American zones of Bavaria, and many of them were the Lucyks’ old friends. A clique formed and became known as the Chiemsee artists, named after the large lake in Bavaria where they realized their inspirations in sculpture, paintings and literature. The Chiemsee is a stone-throw’s away from Berchtesgaden, where Hitler’s Eagle Nest had been seized by the Americans. In exile in Germany, Stepan Lucyk was one of the leading members of the Union of Ukrainian Artists and co-editor of the journal “Ukrainian Art”. His life, my grandmother’s and my great aunt’s contributions are the foundation of The Woman at the Gates. And I used a very special painting, owned by my cousin now, as a symbol throughout the novel.

Very skilled at drawing, Stepan Lucyk acquired a fine sense of color and developed his own techniques of arranging planes and masses of color in integral units, without copying the formal techniques of his masters in Paris. He sought to capture the uniqueness of a specific moment in his subjects in the choice of colors and forms, merging them into the highest forms of composition. His presentation, subjects, lines, and palette captured the spirit of his country and his people.

Stepan was very social. He was known for his chivalry and loyalty to friends, and often passed on the pleasures of life to advance his own artistic career. In St. Paul, he worked for a photographer, coloring in black & white portraits but was unable to advance his career in the United States. Ol’ha went on to publish in various journals and newspapers, as well as books, whose cover art were later designed by my father. My father, in the meantime, had followed in his father’s footsteps and also built his career around the arts.

After I married my Austrian husband, I really wanted to return to that apartment in Northeast Minneapolis. I’d grown up just steps away from the two Ukrainian churches in the neighborhood—one Orthodox, one Catholic—and the Ukrainian school where my grandmother had taught us literature, history and all things related to our Ukrainian culture. She’d put on plays and directed our music program. My father took over the choir later. I wanted to show my Austrian husband all of this, and on a whim, I knocked on the door at that duplex.

The new residents were gracious and let us in. Some things had changed, of course, but I was amazed that the place I’d spent 16 years of my life in was as tiny as it was. Five of us had lived there. My grandmother had banged away at her typewriter into the wee hours and into her 80s in the farthest room, where no heat had reached her and where she’d covered the walls with wrapping paper to soak up the condensation. My brother and I shared one bedroom until I went to university. But most of all, I was impressed at how incredibly well my father and mother had utilized that little space of an apartment. Somehow, on top of everything else they had to fit in there, including my father’s art studio on the winter porch, they had essentially raised us kids in an art gallery.

I have since figured out that I’ve inherited a lot from both sides of my family but from my paternal side, I have my grandmother’s love for storytelling and writing, my grandfather’s and father’s keen eye for composition, and a very pure love for nature to list off just a few.

Today, in the Austrian Alps, I live in a small mountain hut that we bought right after my father’s death. After his funeral, I packed up a number of his paintings, and had them all reframed. Each wall of our house is covered with his watercolor landscapes. My grandfather’s miniature oils are exhibited behind a glass cabinet. Someday, I will take the big paintings home, currently hanging in my mother’s house. My brother and I have already divvied them up between us (he called the castle when he was maybe ten).

My father’s and grandfather’s art take up every inch of space on our walls. Of course they do. It just wouldn’t be home without them.

The Woman at the Gates releases September 2, 2021 and is available for preorder now. And if you are interested in a story I wrote from Stepan Lucyk’s perspective, read An Inventory of Mercies in the Souvenirs of Kiev – Ukraine and Ukrainians in WW2 – A collection of short stories.

Reference: Stepan Lucyk, Artist: Ukrainian Free University, Series: Ukrainian Art, volume 2. Publisher: Lisovi Chorty, New York, N.Y. 1973

Title photo: Castle Neubeuern in Neubeuern, Bavaria. 1946. Stepan Lucyk, part of the Lucyk Family collection (that one’s going to my brother; I think he called it when he was ten years old; the first time he came to visit me, I took him straight there.)

AN EXTRACT FROM

The Woman at the Gates

From Chapter 3

That weekend, as the church bells rang all around the city, Antonia crossed Kosciuzki park with Viktor. The air was scented with the last of the lilacs, but the garden’s tulips and daisies were already replaced with foxglove and begonias. There were plenty of people out for a stroll or hurrying—as Antonia and Viktor were—to their extended weekend celebrations. It was Lena who had suggested they come over for nalysnyky, Viktor’s favorite. Antonia’s sister usually made a selection of the crepes with both savory and sweet fillings.

A man with a little brown dog on a red leash passed them, followed by a woman with a pram and two fair-haired girls in tow, their braids bouncing over their shoulders. On the other side of the park, a group burst into peals of laughter. To the left, another group was singing. The atmosphere was cheerful. Antonia hooked her arm into Viktor’s and smiled.

When they reached the art studio in the Sofiyivka district, Antonia noticed the boxes of frames and supplies stacked outside the door.

“Roman’s exhibition starts next month,” she said. “It will feature a selection of his Galician and Hutsul paintings.”

“Including the portrait you sat for?”

“Yes. And he’s going to ask the artist’s union for permission to travel abroad. But you know Lena. She’s anxious about being left alone, especially with the baby due in a couple of months.”

Viktor gave her a reassuring squeeze. “Maybe she can go to Sadovyi Hai for the summer.”

At the apartment building, Antonia removed the spare key Lena had given her to avoid having to climb up and down three flights of stairs in her condition to let them in. Before she pushed open the door, Antonia halted at the sight of a brown dog coming around the corner. It was the same one that had passed them in the park. The same red leash. And the man with the hat—short-legged and round like the dog, he was the same, too. He did not look at them but hunched into his coat as he passed the apartment building.

Antonia put a hand on Viktor’s arm.

“The dog,” he said in a low whisper.

“Do you think Major Vasiliev is having us watched?”

His eyes narrowed, but Antonia stepped back onto the walk, pretending she’d dropped something. When she turned her head, the man and the dog were disappearing through an apartment door further down the block. A coincidence then, but she could not shake the foreboding. As they climbed the stairs in silence, Agent 1309 popped into Antonia’s head. Where was he? And what had he managed to accomplish in the past three months?

She had no chance to mull it over as Lena opened the door before they could even knock. Behind Antonia’s sister, Konstantin zipped across the hallway, dark hair bouncing. The five-year-old threw her a woeful look before yanking the sitting-room door open so hard that the translucent window rattled in its frame.

Roman called from the kitchen. “The least you could do is greet our guests, Konstantin. Where are your manners?”

“Someone’s not happy,” Antonia remarked when her brother-in-law appeared.

Lena smiled apologetically and invited them in. Everyone embraced and kissed each other’s cheeks before Roman gently pulled Antonia aside and pressed something cool into her hand.

“Is it finished?” She opened her palm to the gold locket. The piece had cost her a small fortune, but it was what was inside that made it valuable. She released the catch and it popped open. Antonia stifled her pleasure. Roman had finished the miniature of her portrait. She had sat for it several times, and it had taken him many painstaking hours to complete it, but here was its tiny copy, and it was beautiful. She held it up close, her back to Lena and Viktor. The tiniest strokes of the brush depicted the red highlights of her hair. He’d even put in the brown and gold flecks of her hazel green eyes—tiny, tiny strokes but masterfully done. The background was lapis blue. Roman had also managed to depict the top part of the orchid pin she’d worn on her dress.

She pecked Roman’s cheek. “Viktor will love it, I’m certain. I’m going to give it to him tonight.”

Antonia shrugged out of her spring cloak. In the sitting room, Konstantin was lining up his tin soldiers along the coffee table, quietly humming to himself.

“What’s gotten into my nephew?” she asked Lena. Usually he threw himself at her.

Lena and Roman exchanged a look before Lena hung up their coats.

“He wanted a puppy, and we said no.” But Lena’s grin was mischievous and she tugged at her earlobe. Antonia bent down to be eye-level with her. Her sister was terrible at keeping secrets.

“What is it?”

“We’re going to get him one, but only after the baby comes. And we’ll do it when we’re back in Sadovyi Hai for the summer.”

Antonia watched the men drift into the sitting room, then steered her sister into the kitchen. Lena rubbed the sides of her belly.

“Are you well?”

Lena said she was, her eyes on Antonia’s flowered scarf. “And you? It hasn’t gone away, has it? Will you have it removed?”

“I don’t have the time.”

Ignoring Lena’s exasperation, Antonia leaned over a bowl of fresh berries and plucked one.

Lena playfully smacked her hand. “We pray first.”

“I have a little happy news myself,” Antonia said, snatching a piece of cheese off the platter. She turned her back on the kitchen door and whispered, “I just happened to be cleaning out Viktor’s suit coat pockets…”

“You did not!” Lena admonished. “Antonia, you know I don’t approve of you behaving as if the two of you are married. And even if you were married, what are you doing going through his pockets?”

“I was only getting his suits ready for cleaning. Some I need to mend.”

“And?”

Antonia could hardly keep a straight face but looked meaningfully at her sister. “I found a box…”

Lena gasped.

“Inside, a beautiful, simple diamond—”

“Goodness.” Lena gripped her by the forearm. “But he left the Church. And you… well, I can’t remember the last time you’ve been.”

“Don’t start.”

Lena let go of her. A strained smile. “When do you think he’ll ask you? Will you say yes?”

“I’ve decided I will. You know, we met on Pentecost weekend three years ago. This morning, he referred to you as his sister-in-law. ‘I can hardly wait for the sister-in-law’s nalysnyky,’ he said this morning.”

“I thought he swore never to marry.”

“I swore I would never marry,” Antonia reminded her. “It’s romantic, him hiding the ring. I thought you would be delighted.” The most romantic thing Viktor had ever done for her prior to this was put a bouquet of forget-me-nots into an Easter basket.

Lena tugged her deeper into the kitchen. “You challenge one another in so many ways; that competition could very well be bad for a marriage.”

Antonia pulled away from her, but Lena went on, “Viktor is a good man, and you make a strong couple, both headstrong, ambitious, intelligent…”

“And? What’s wrong with that?” Antonia said sourly. “We’re not romantic enough for you? I’m the big sister here, remember? Not once did I share my reservations about Roman and you.”

“I worry that your egos and not your hearts attract you to one another, that’s all.” Lena placed a cool hand on Antonia’s cheek. “I wonder whether you will both vie for power and end up resenting the other when one of you must step back.”

Six voices. Six stories. One portrait.

The award-winning collection. Join poets and partisans, artists and dissidents as they navigate their way through WW2 Ukraine. Available now in all formats!

Kate Baxter

June 27, 2021 - 7:07 pm ·Such a tremendous and wonderful legacy. Thank you for sharing your stories with us.

Chrystyna

June 28, 2021 - 5:02 am ·Thank you for reading them!

Tonette JoyceSkube

June 29, 2021 - 6:54 pm ·A wonderful excerpt to a story that I have had my eye on. And oh, the wonderful family story! I can feel what it must have been like surrounded with the art and the atmosphere of the home. ALL second-gens that my mother grew up with, (as well as her family), were bilingual, most, including her family, awaiting the day that they would ‘return’ to the home country. In my mother’s case, the parents hoped to take everyone back to Umbria, but they also had Polish, Ukrainian, German, Russian and many other expats in their neighborhood who hoped to do the same.