I grew up in the Ukrainian diaspora of Minneapolis, Minnesota (U.S.A.). The neighborhood was called “Nordeast”, the Slavic-accented pronunciation of the neighborhood where two Ukrainian churches were located right across the street from one another: St. Constantine’s, the Byzantine Catholic one* and St. Michael’s, the Orthodox one. Sometimes, when the parishioners from the two churches met in the middle, even the trees bowed out of the way. There was that much tension between the archaic believers that one rite was more right than the other.

I grew up in the thick stew of Ukrainian nationalism, too. There are at least a half-dozen factions for that as well, each one stating they are more patriotic and have the better intentions for the country than the other. My mother’s and father’s marriage alone forced my brother and me to take a front row seat to the spectacle of infighting. My mother was Orthodox Christian. My father was Byzantine Catholic. Add to the mix my Polish relatives and we were assured fireworks at every holiday, regardless whether we were visiting my father’s side of the family or my mother’s.

I grew up with what might today be considered “old world values”. My father hammered into our heads that first came God then family and, only after that, our friends. Some of my friends—including later my own spouse—could not understand how my brother or I could just spring at a moment’s notice if someone in the family needed us. But we did. And 52 years later, I still do. For family and for friends, and because of my upbringing, those closest friends are often considered family, so the lines seem always blurred.

My nephew, Alex, at my parents’ house one Easter. A rushnyk is the embroidery around my grandfather’s painting behind Alex, or on the cabinet to his right.

I grew up with a very superficial understanding of what it means to come from a family of Ukrainian war refugees. The struggles, the hardships, where we came from—that was no secret. I heard about it on every occasion. We sang songs about it. We recited folklore and poems about Ukraine’s centuries-long struggle for freedom from oppressive rulers. We took oaths. As a child, I was absolutely convinced that I was a Ukrainian first, and an American only by happenstance. I argued with my fifth-grade teacher about it. “Our people” were fighting to free Ukraine from Russia’s enslavement. My family and I were all just waiting until we could return to the “home country”.

I grew up floating between two totally different worlds, the boundaries of which were as simple as crossing from the living room into the dining room. Truth is, I am an American. Born and bred like Bruce Springsteen. Stars and stripes and red-hot freedom is in my blood. Between the borscht and pyrohy, marathon Easters, and vodka, there were the Fourth of July, hot dogs, and apple pie. To my grandmother’s consternation, my boyfriends were also Americans. (Babunia: “Why can’t you find yourself a nice Ukrainian boy?” Babcia, who was my father’s mother, loved anyone that I happened to be in love with. She was always just hoping I’d find my Happy-Ever-After.)

I grew up 100% American from Mondays to Fridays, and 100% Ukrainian from Saturday morning and Monday nights. On Saturdays, I attended Ukrainian school, Saturday afternoons were for Ukrainian scouts, Sunday mornings for church—sometimes at both churches—followed by long, long Sunday lunches at someone’s house from the “gang”, where we kids experienced every type of rite of passage, Ukrainian and otherwise, whilst the “gang” – the kids who saw WW2 but could do nothing about it – sang and drank.

And Monday nights were for Ukrainian folk dancing lessons, the highlight of which was the annual encore performance at the St. Paul Festival of Nations. Oh, and we spoke Ukrainian at home. Which, as my brother and I hit our teens, turned into a mish-mash of our own unique Ukrainian-American slang (well, unique to us and those kids from the “gang”).

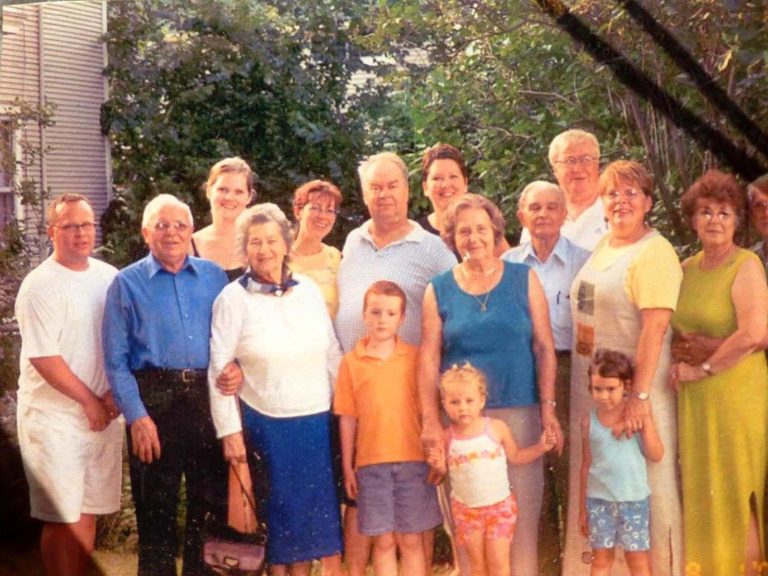

My husband (L) and my Streiko Roman (my father’s brother, and the inspiration for Nestor in The Woman at the Gates). My mother’s family is in the background, including Uncle Pete (little guy on the right). He is the real-life person behind my character, Kulka, who appears in both The Woman at the Gates and Souvenirs from Kiev.

I grew up loving it all. These were my worlds. I was good at choosing and selecting what I needed to my advantage and when. I loved the temperaments, the hefty political discussions, the love which not only came from affectionate hugs and three kisses on the cheeks, but also from an incredible amount of tradition, food (lots of food) and, eventually, drink. (Typical conversation when my husband and I return to visit: “Come in! So good to see you! I made food.” “We’re not hungry. We just ate at your sister’s.” “Then, vodka. Or do you prefer scotch? And I’ve only made some cabbage rolls. You eat.”) If this sounds like My Big Fat Greek Wedding, I’m going to tell you a little secret: my sister-in-law and I went to see that movie together. The two of us were laughing-screaming so much that we had to buy another round of tickets to watch all the parts we missed. She’s American, by the way. Her experience was not much different to that of the WASP-fiancee in the movie.

I was raised by a family who wanted nothing but the very best for me. By the time I graduated university with a semi-journalism and semi-biology degree, and a hobby interest in the psychology of human relationships and history, I believed I had a pretty good idea of what we were all about. So, when I sat down with my relatives to record their experiences with the intention of writing a book, I thought it would all be a piece of cake. I knew these people. My goodness, I grew up with them.

I have, to this day, never been more wrong about anything in my life.

I won’t lie. When Manfred pulled out a guitar and played the first time, I was instantly in love. They say a daughter looks for someone who reminds her of her father. And there was so much more. My heart…

The complexities and problems that the Ukrainian diaspora faced, immediately post WW2, had indeed become diluted by the time it reached the first-gen Americans. After I had over 60 hours of recorded interviews, I came—at the tender age of 25—to the conclusion that I knew “nuthin’”. Heck, I knew less than nothing. Fast forward a marriage, a divorce, a job I loved and a job I hated, and then jumping ship to travel around the world. I found those interview tapes as I packed, sat down on my rented bed, and popped in the first cassette.

It took me all of four minutes to figure out that the reason I was going to Europe, and alone, was to get this thing done. I was going to write this book. Mainly because I’d promised my Babcia—also a writer, and a poet, and a musician—that I would “tell her story.” It was also clear to me that, to write that monster, I had to at least experience something that these people had. I had to learn about the world, period. I had to really figure out who these people—with whom I had celebrated every birthday, every Communion, every Christmas, Easter, fight and debate, you-name-it—who the heck they were. What had shaped them. What had made them grow up into who they were.

When I called from Austria to ask my parents to sell my car and send money, that I was moving here permanently, my mother laughed. “Okaaay. So, you’re just closing the circle?” (She was born in a DP camp in Gnigl in Salzburg.) I tried to explain that I was absolutely certain this is where I am supposed to be. Something had been drawing me to Europe for as long as I could remember. Maybe it was the atmosphere I grew up in. Maybe it was my imagination of the “old country.” Or maybe, like my Babcia, I was a little clairvoyant and just looking for my Happily Ever After. Because I grew up, somehow knowing, that the love of my life was waiting for me “over there.”

My husband and I married outdoors in the area where I first fell in love with Austria, the Bregenzerwald. I wore a juppe, a traditional dress for the region and the Ukrainian blouse I purchased in Lviv during one of my visits to Ukraine.

My Babunia. My maternal grandmother. She was in the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists under the Polish regime, saw her friends viciously killed, and after the Blitz, hid in a pile of cow manure as Nazi patrols hunted for her and her brothers – one who’d deserted the Wehrmacht. She’s 98 today. When I ask her how she’s doing, she says the same thing she’s been saying since she was 65: “Oh, honey. I don’t know how much longer I’ll be in this world. And I just can’t do the things the way I used to.” My answer never changes either, save for the number. Like this year, “Well, yeah, you’re not 97 any longer.”

Part of the family. My grandmother, Babunia is in the center in the blue tank top.

Spoiler: 7 years later, I learned I was right. I met Manfred and when he introduced me to his rather large family, I discovered they celebrated such similar traditions that I felt like I had come home. Like my father and my uncle, Manfred plays the guitar. Like my family, his laughs loud and boisterously, jokes heavily, is gracious and generous, and they all sing.

My husband’s name is Manfred. My romantic Babcia sadly passed away many years before. But during our first visit, my Babunia observes Manfred from afar and, once in a while, smacks her lips. Then she comes to me with that grin I knew is used to buffer the critique.

“This the man you marry?”

“Yes, Babunia.”

“Ah. Well, he nice guy. But, Chrystyku? You never find just nice Ukrainian boy?”

“Babunia, I’m 40. Besides, if it makes you feel better, I live closer to Ukraine than ever before.”

She laughs. She looks my husband up and down, pulls him in close as if taking possession and says, “I like this man. He nice man. It’s okay if you are Austrian. We call you Fedir now. It’s all okay.”

(BTW, Manfred’s first wife was Swiss. Back then, his father had asked why he couldn’t have found a nice Austrian girl. The Swiss dialect is hard to understand. After Manfred met me and told his father he was now proposing to an American, his father complained even louder. Today, I’m the only daughter-in-law allowed to give him three kisses.)

Manfred has embraced my Ukrainian-American heritage as I have embraced the Austrian. We prepare baskets at Easter for blessings at the church, including hand-painted pysanky, and since my father’s death, I have taken over the art of Ukrainian sausage making (just lots of garlic, loads of garlic). At Christmas, I set an extra plate for the dukhy – the spirits of our departed, or in case one of our friends or neighbors pops by to partake in the 12 dishes because to me, everyone is simply family. Those dishes include borscht, pyrohy, nalysnyky, cabbage rolls, beet salad, my husband’s Venetian fish, pea and sauerkraut salad, and kutia. My father’s paintings hang on our walls, recreating that art gallery I grew up in back in Minneapolis. I still set out the embroidered rushnyky my mother embroidered for my first wedding.

Over an ocean and thousands of miles from home, but closer to Ukraine than ever before, I continue to celebrate the rich heritage and traditions I have picked up from my immigrant elders. My greatest joy? Seeing my family in the States and laughing with them. Or when Manfred’s kids come for the holidays, or our friends come to the Orthodox Easter brunch, and everyone is looking forward to the Ukrainian-inspired delights. Because the way I grew up? Nothing is more important than sharing with loved ones: Our food. Our lives. And most of all, our stories.

“Because we cannot know who we are if we do not understand where we came from.”

*If you happen to click onto that link for St. Constantine’s and peruse the gallery: my father helped paint that church and the art of using gold leaf and the symbols was taught to him by a master painter from Chicago, who also knew my grandfather well. My grandfather really did help refurbish the frescoes of a chapel in the Slovakia during the war and received a wagon-load of food in return.

Featured image: edited, original file by Andrew J.Kurbiko, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons

All other images from family archive

Six voices. Six stories. One portrait.

The award-winning collection. Join poets and partisans, artists and dissidents as the navigate their way through WW2 Ukraine. Available now in all formats!

Pamela Allegretto

July 23, 2021 - 5:50 pm ·Such an enjoyable, fascinating post. My compliments.