Meet the women Who inspired

Antonia and Lena in

The Woman at the Gates

Here’s the thing: when you’re young, you are likely to be so self-obsessed with your own growing up, that you don’t really pay attention to what really matters to the grown-ups around you. It’s even more so when it’s your grandparents. I don’t recall when I became conscious of the fact that my live-in grandmother was an author. When I finally did, I still don’t think I really registered what it was that she really did other than be my grandmother, or my father’s mother. It took writing three novels about WW2 Ukraine in which she is featured as a major character to even make the connection that, like me, she wrote historical fiction. I don’t even know whether that was considered a genre in Ukrainian literature. Maybe I’m wrong. Maybe questioning that reveals my ignorance even more.

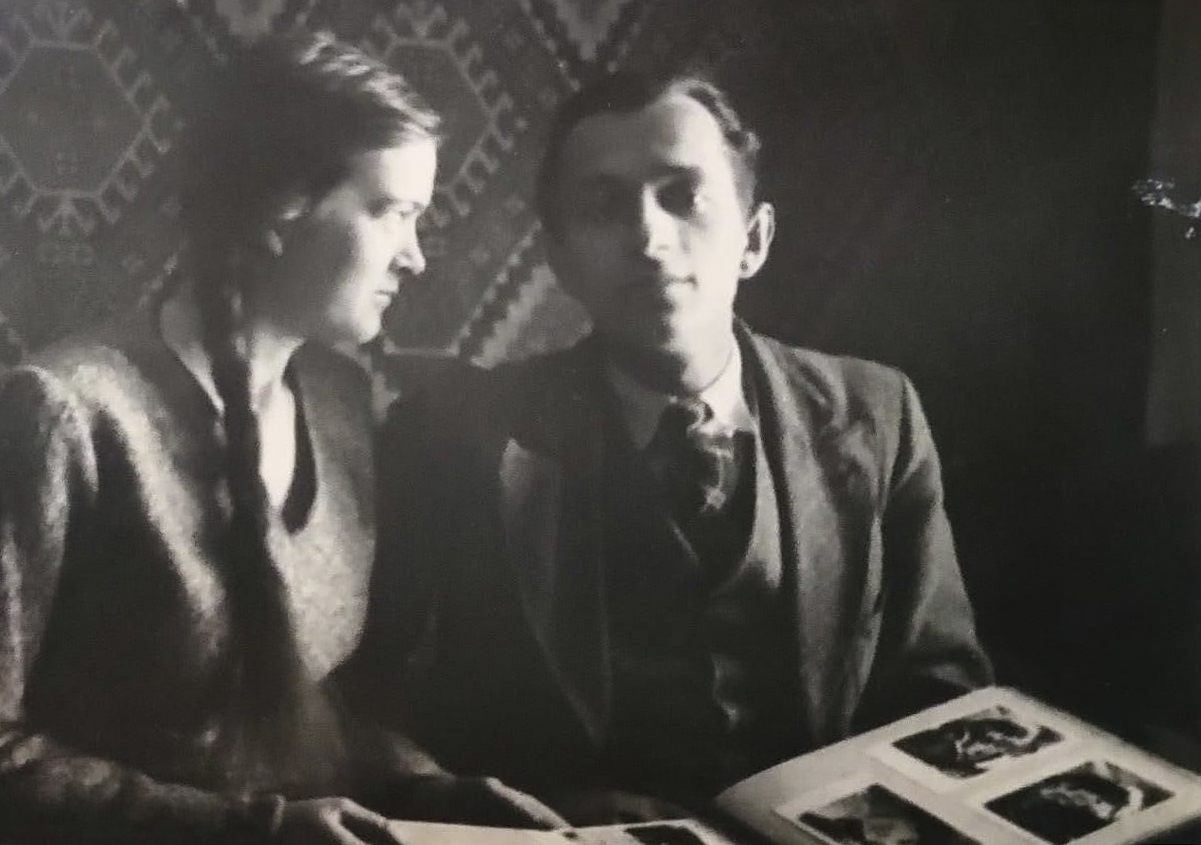

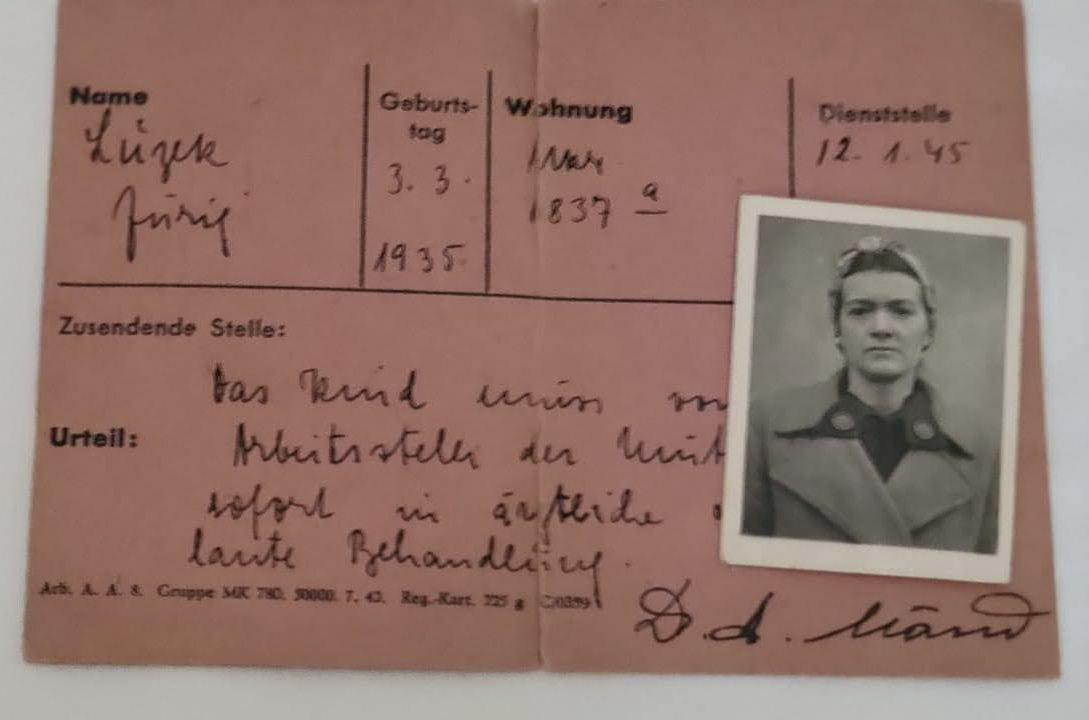

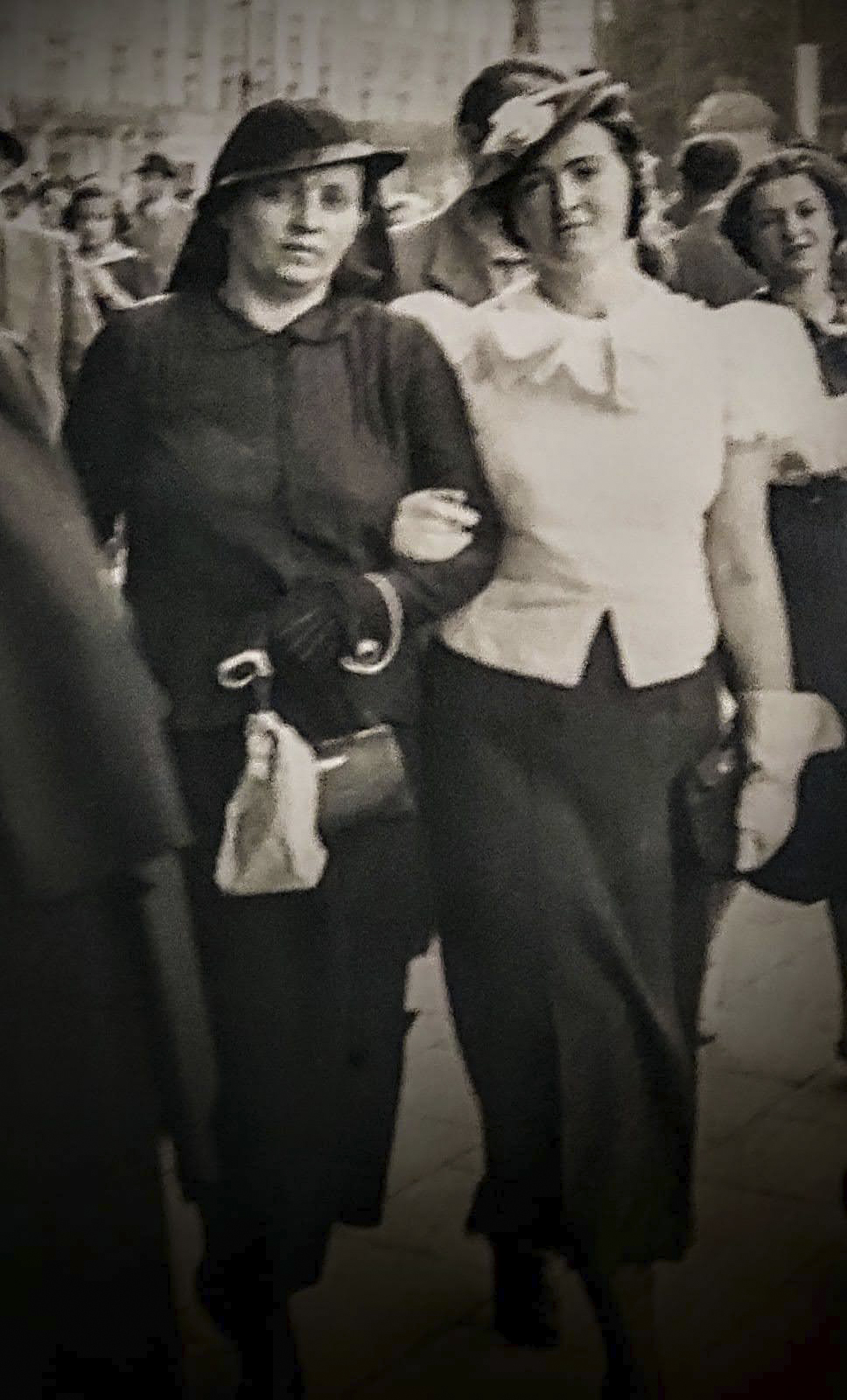

Olena (Ol’ha) Remenets’ka Lucyk (pen name: Olena Rem). In the 1920s portrait of the two women, my grandmother is on the left, her sister Antonina, on the right. However, when I was writing The Woman at the Gates, it was Ol’ha’s image I used for Antonia and Antonina’s image for Lena. In this way, I spliced the two into separate fictional characters, drawing on the characteristics I wanted to use for the two sisters in the novel.

But even without her work, my grandmother Ol’ha, or Babcia as we called her, was a huge personality. She was genteel, graceful, dignified, and a romantic to the bone as well as very funny.

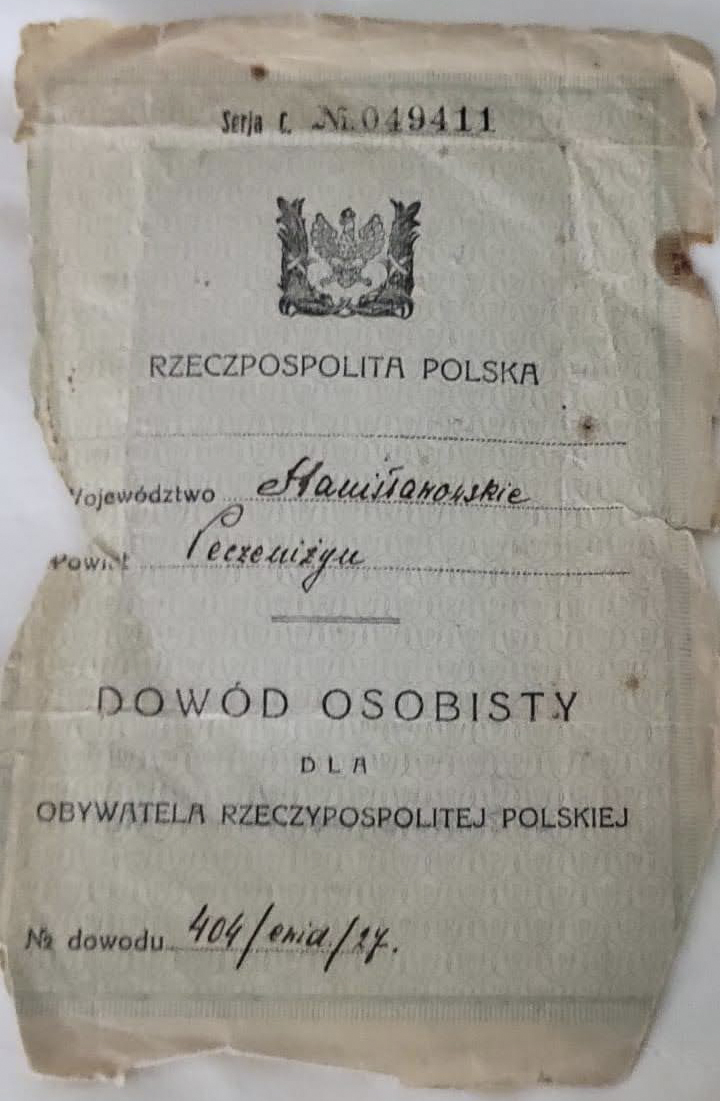

My father told me their story, her story. Unlike in the western Austrian culture, within which I now live, my Ukrainian relatives were not mum about their experiences in WW2. On the contrary, how they arrived to the U.S. and what they’d survived was ever-present in my immediate and extended households. My family wanted the kids to understand where we came from, why we attended Ukrainian church and Ukrainian school. Why our love for Ukraine had to be kept aflame. Because at least into the late 70s, the older generation believed we were all “going back.” Except it took nearly another 15 years before Ukraine’s borders were opened and it was safe enough for my Babunia, my maternal grandmother, to visit her long-lost family members. My mother made that trip with her. And it was clear to everyone there was no going back. How do you voluntarily return to a country that was 50 years behind the times compared to the west?

Further, my Babcia Ol’ha had firmly established herself in our Ukrainian diaspora. I was always surprised by – and a little proud about – how renowned she was. When we met with Ukrainians from Chicago or New York or Toronto, Babcia was received with warmth and an awe that is attributed to artists: she’d written books, plays, articles, short stories and composed music and songs, sang in the Dnipro concert choir, directed, and taught history and literature at the Ukrainian school. Amongst Ukrainians, she was note only known, she was very much loved.

Ol’ha and her husband, Stepan Lucyk, who was a renowned painter. They met while he was painting in the Carpathian mountains. The fictional village of Sadovyi Hai is based on Lanchin in western Ukraine.

I remember Babcia’s typewriter clacking away in the room down the hall from mine. Sometimes at 3:30 in the morning, I’d wake up to it and pad over to her door and she would blush and apologize. She was trying to type quietly. Not an easy feat on a typewriter.

When I began writing my own stories, she was delighted and would listen to them, then encouraged me to write them out on her typewriter. It was a Ukrainian typewriter. My stories as a child were in Ukrainian. I knew those letters and could type before I had a class in junior high “American” school. It was getting the Latin keys right that was the challenge. And soon after, I was writing stories solely in English.

When I was in college, she suffered from congestive heart failure. I rushed from Montana to her bedside in Minneapolis. She took my hand and said, “Kotyk, I want you to share my stories.” I promised her I would, thinking I would spend the rest of my life translating her piles of manuscripts stored in countless boot boxes beneath her bed. It took me four or five years to understand that was not what she intended; a visit in a dream where she said, “I want you to tell my story.” And that was when I sat up and started paying attention.

I unfortunately do not have any photos of Antonina other than the one portrait, but I found these photos in a shoebox years after Babcia passed, and when I started interviewing my other relatives to get their stories down. The photo of my grandmother and my grandfather in front of the house, however, was taken in Deliatyn, in the Carpathians. It was where Antonina was teaching, and where my father’s kindergarten teacher was murdered by Banderites, her body dropped into the well outside the house. This event also takes place in The Woman at the Gates. My father then told me that Antonina was so disgusted, she wanted to stop working for the OUN entirely.

So, I decided that – as a journalist student – I’d start researching my family’s history.

My mother immediately jumped on the idea and said, “Why don’t you go talk to your other grandmother and record her story.” Before it, too, was too late. And suddenly I had so much material – because after speaking with my Babunia, she would sometimes say, “You’d have to ask your great uncles about this or that…”

My Babunia, in June 2021, turned 98. And she is still going strong. In other words, I’d have had plenty of time but am I glad I did what I did when I did it.

Because I was finished recording my mother’s family, and preparing to move to Austria, my father drove me down to Chicago several days before I’d board the plane and leave the United States. We spent days talking about his parents. That was also when I’d learned about a lot of people I’d never known.

But one person stuck. She stuck so hard, The Woman at the Gates is based on her. My father spoke warmly about his aunt, Antonina Remenets’ka. He told me how, in the 30s, she joined the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists (OUN), and risked her life to save the persecuted intelligentsia. Antonina, as genteel and witty as her sister but also much more of a risk-taker, could drink Soviet officers under the table. She danced with them, charmed them, then stole lists of the names containing the targeted victims. Later, she did the same with the Nazis and saved many lives. Had she ever married, I wanted to know. My father told me she had not. She’d been very much in love with an Austrian veteran of the First World War and he’d been killed on the border, trying to get the very people Antonina arranged to help into the west. She died after the war, when the American DP camp officials sent her to the hospital in Munich to take care of her goiter. She died of an infection that could have been cured had there been penicillin available.

My grandmothers, my family and me. The white-haired one is my Babcia, Ol’ha Lucyk, and Maria Pundyk Smaha is my Babunia, the one in blue.

In The Woman at the Gates, Antonia was inspired by my father’s stories about Antonina. Lena, in the novel, was inspired by my grandmother, Ol’ha.

I have a photo of the two women on my desk that I have dragged through four different countries as I slowly made my way—and my life—to Austria (upper slide show, 1920s). When writing Antonia, I used my grandmother’s image. That strength and determination in that look in the portrait was what I wanted to bring across. I combined what I knew about my grandmother and my great aunt into the one character, spliced it and created Lena, which, in my mind, was the woman on the right. My grandmother was also older than Antonina. I reversed this in the novel. Antonia is the older sister to Lena. There were a whole lot of features and aspects that I also pulled from many other women in my family: my Babunia was also a member of the OUN in the province of Vohlyn. She is resilient and resourceful, often no-nonsense but has a good sense of humor. Her personality and characteristics also seeped into Antonia as I wrote.

Ever since my father told me about my great aunt Antonina, I’d felt a great affinity to her. He told me once that I reminded him very much of her and maybe that has something to do with it. It has been difficult enough to admit how little I knew about the very people living under the same roof and then, reaching into the beyond, to recreate people I’d never met. Sometimes, I worry about doing them a disservice. Other times, I think that maybe I’ve finally made good on my promise to my Babcia. After all, isn’t it our stories, our imaginations that keep our loved ones alive in our hearts and minds? I think that’s what she wanted.

They took her country.

But they will never take her courage.

Releasing September 2nd. Prefer the audiobook? You can listen to the prologue now! Or download the first three chapters for free here.

Six voices. Six stories. One portrait.

The award-winning collection. Join poets and partisans, artists and dissidents as they navigate their way through WW2 Ukraine. Available now in all formats!

All images from family archive