My maternal grandfather, Youry (George) Pundyk died when I was just four years old. I was at my grandparents’ house when he passed. I’d been playing “nurse and patient” with him not more than an hour beforehand. I had a red pencil and dipped the tip into a glass of water to give him his “shot” and “draw blood”. For my work, he paid me a quarter and I went to the local candy store with my uncle to buy a package of my favorite candies. They were called Charms. Each rock hard candy looked like a precious stone: ruby, emerald, diamond, amber. And each was wrapped in pretty cellophane. I coveted them and couldn’t wait to be able to play nurse again so I could get another quarter and collect further jewels for my “treasure”.

I’d just returned when there was a shriek from my grandparents’ bedroom. I remember only a lot of adult bodies, sobbing and pleading, as they were trying to lift something heavy off the ground and back onto the bed. My grandfather.

I scrambled under the kitchen table to hide. I remember the sound of the ambulance. The gurney wheels rolling past my face. Twice. Once in. Once out. And then my grandfather was gone. Forever.

Whilst writing The Woman at the Gates, it was not until I was reading the 7th or 8th draft that I realized how much of my grandfather’s legacy had influenced my characters. The surprise was this: it was my father’s side of the family’s history I was writing but, not for the first time, I realized I’d mashed up a number of real-life personalities into my novel’s cast.

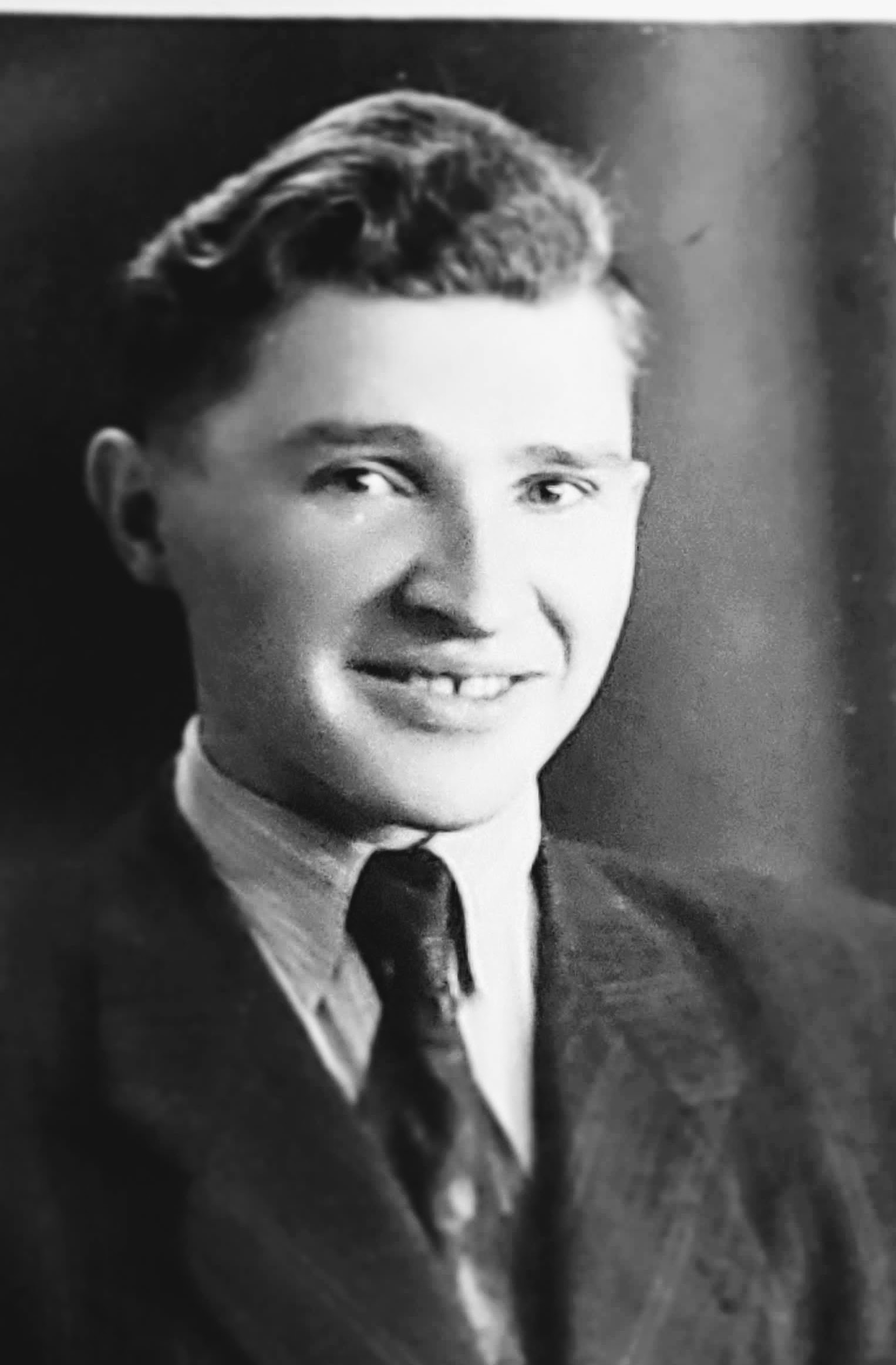

Viktor Gruber – the Austrian professor who works with Antonia and is her love interest at the beginning of the book – was based on the phantom Austrian veteran my great-aunt is said to have been so madly in love with that, afterwards, she swore she would never marry. Her lover had been tragically murdered on the border while helping Ukrainians flee for their lives from the regime. Instinctively, I have always believed that she felt responsible for his death. This is something that I layered into Antonia’s character in the novel. What I didn’t expect – in the reading of that late draft – was how similar both Antonia and Viktor were to my mother’s father, the one who’d tragically died when I was four. Over the years, as I was growing up, my mother’s family had shared proud snippets about Youry Pundyk and I realized that I had subconsciously added elements of him in: my grandfather ran a Ukrainian nationalist paper, an inspiration for the novel’s “New Voice” printed by the underground rebels. He was head of a spy ring. He was a professor. A very well-educated man who spoke many languages. However, I think his story is best told by the people who were closest to him. I may have immortalized his legacy but I asked my mother to bring my readers closer to a man I’d barely known.

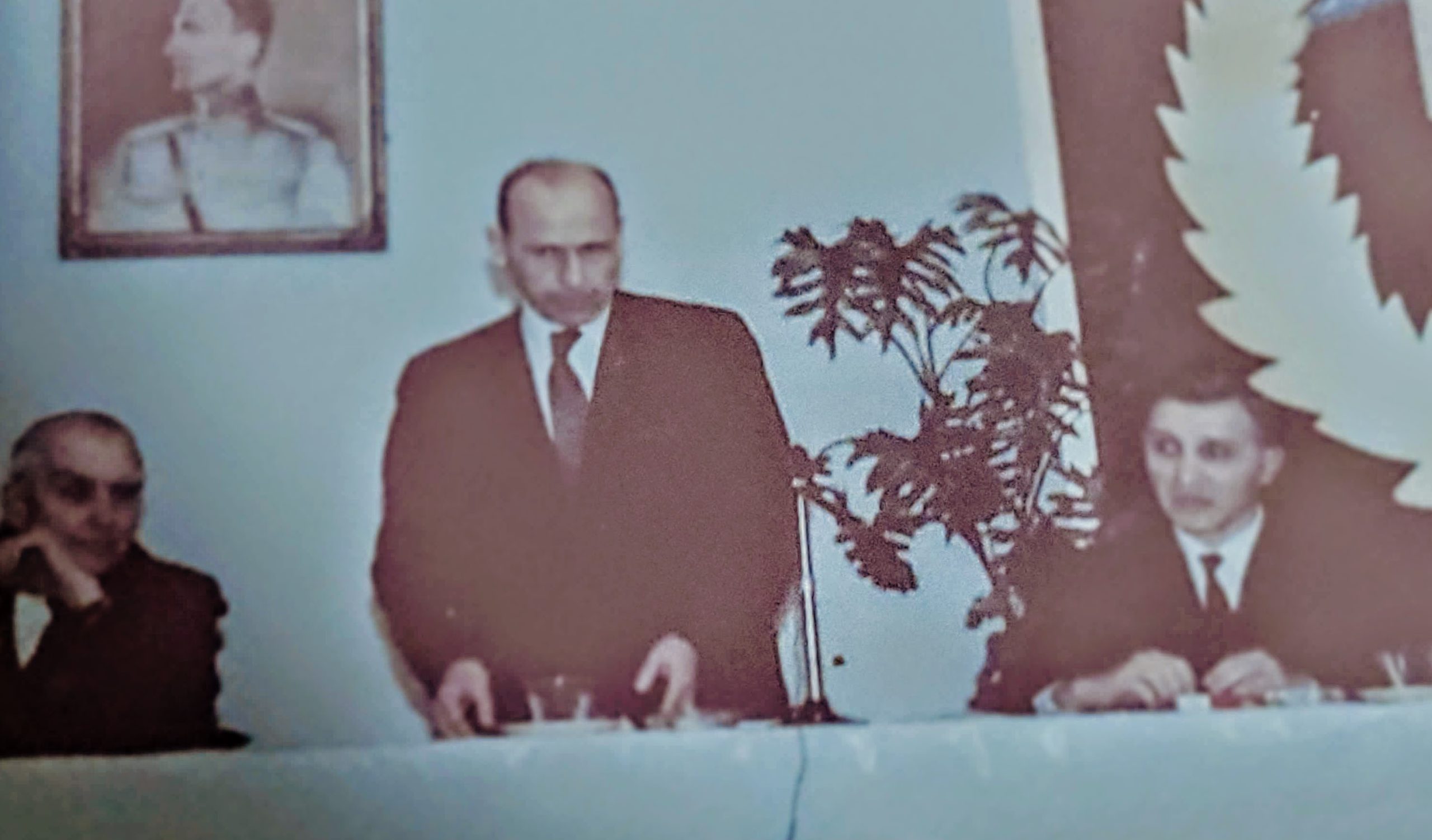

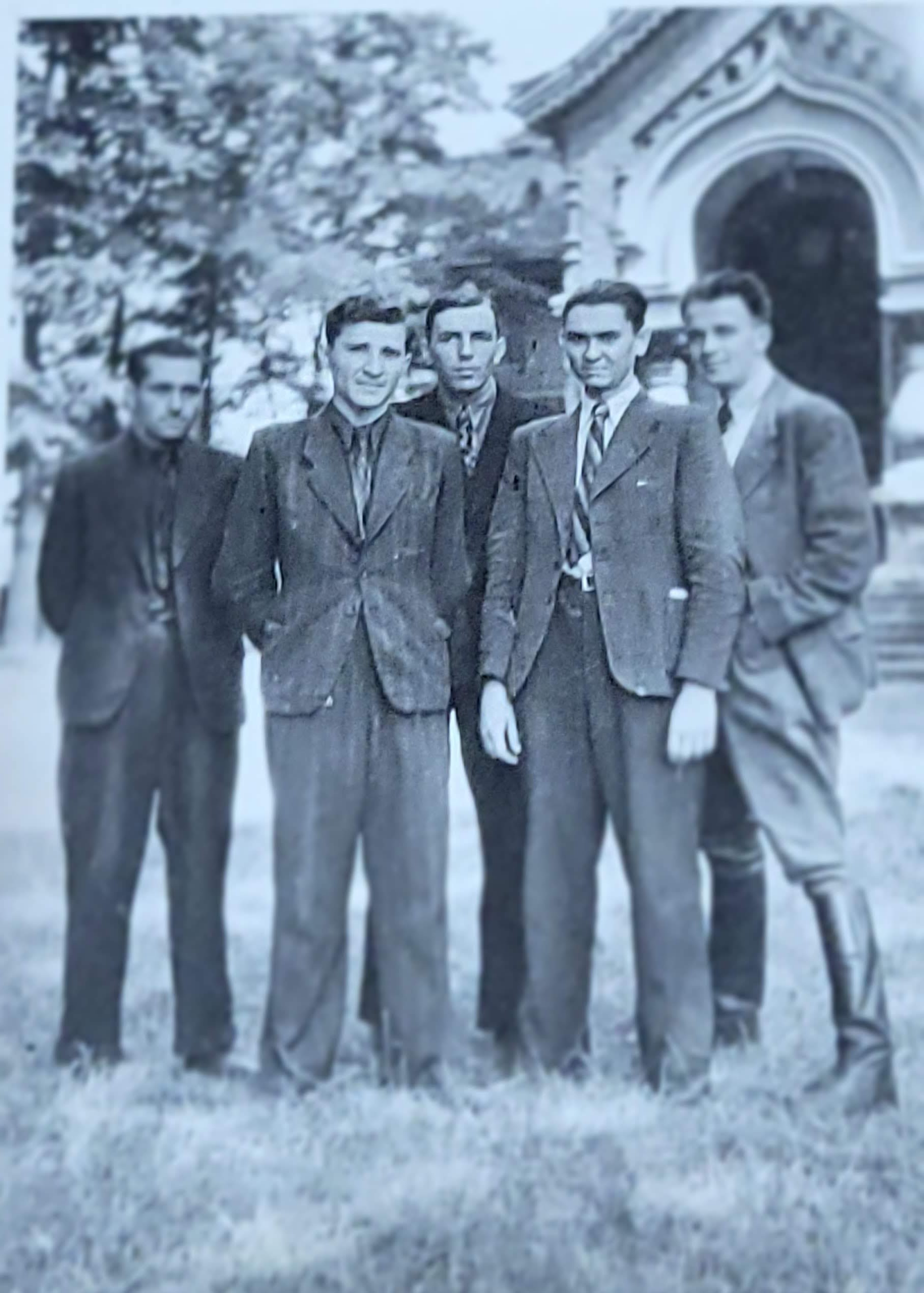

The three men pictured in the featured image above include (l-r): my Google images search for what I thought Viktor Gruber might look like, my grandfather Youry Pundyk (mother’s father, and someone from my paternal grandmother’s shoebox full of photos. I use tons of images while writing.

by Lesya Lucyk

My dad was a gentle man with a dry humor that first stunned and then drove everyone to laughter. Sometimes he liked making a fool of himself, such as when he participated in a talent show with other teachers at the junior college, doing a Hawaiian hula dance in grass skirts, or another time – when my mother, as a joke, presented him with a new dress she had bought for herself as his birthday gift. He suddenly disappeared from the party and when he returned, he was wearing her outfit. Everybody died of laughter and my mother was embarrassed. But he was a gentle and private soul – a true diplomat who treated everybody equally and with respect – from an iron miner to the most intellectual person in the world; from people who agreed with him to those who fanatically disagreed with him. He used to say, “Diplomacy is telling a person to go to hell and they look forward to doing it.”

However, his passion really lay in protecting Ukrainian nationalism and culture and he used his intellect and talent for writing to influence others – to teach them the philosophy about democratic nationalism and how we must fight to protect our Ukrainian culture, traditions and – most of all – language as it was under threat of disappearing and being replaced by Russian. He always believed Ukraine would eventually free herself from Soviet tyranny and when she did, he envisioned there would be an army of those devoted to govern her democratically.

Youry (George) was born in the small village of Perchirnya in the Volyn region of Ukraine. His family was very poor but a teacher in the village recognized his intelligence and, when he finished “grade school”, he made arrangements for my father to study in a seminary in Krementz, where Youry graduated with honors. He went on to Berlin to attend university. There he met other Ukrainians who had formed the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists (OUN).

When Germany invaded Ukraine, he returned to Volyn and became a leader of a spy network for the Ukrainian partisans. As the Soviets started defeating the Germans, he had to flee westwards and ended up in a displaced persons camp in Salzburg, Austria. There he became involved in publishing a camp newsletter called “Promin” and served in the camp’s administration. During the registration of new arrivals, he met my mother, they got married and had a daughter – me. In 1947, we went to Munich, where my father got involved in publishing “Promin” as now an official newspaper and that eventually became “The Ukrainian Voice” (Ukraiinskyi Holos – in Chrystyna’s novel, she used “Our New Voice”). As the Ukrainian national movement evolved into two factions, my father became active in the Melnyk faction, which propounded a more democratic view for Ukraine.

Throughout his life, he wrote many articles to Ukrainian newspapers, even contributing to a satirical newsletter called “Arkan” – using his humor. These articles were compiled in a book called “Ukrainian Nationalism” and after his death another book of his articles was released. They influenced generations of Ukrainians and he was considered the philosopher of Ukrainian nationalism. He traveled to France, South America and Canada and lectured to audiences eager to hear from him. His passion for Ukraine and his causes were his life’s work.

In 1949, we emigrated to the United States, specifically to Minneapolis, MN. My father, a linguist, learned English and entered the Master’s program for Economics, at the University of Minnesota from which he graduated a year and half later with honors. He got a job at Hibbing Junior College in 1955 as a professor, and he spent the rest of his life teaching students at the college. A brain tumor took his life in 1973. He was only 57.

They took her country.

But they will never take her courage.

Releasing September 2nd. Prefer the audiobook? You can listen to the prologue now! Or download the first three chapters for free here.

Six voices. Six stories. One portrait.

The award-winning collection. Join poets and partisans, artists and dissidents as they navigate their way through WW2 Ukraine. Available now in all formats!

All images from family archive