Last month, I posted the first of two parts regarding the Catholic rituals and heritage of Palm Sunday through Easter Monday. Having grown up in a Ukrainian-American household in Minneapolis, Minnesota, and then moving to Austria, I have acquired quite the multi-culti layer of practices and experiences.

In this instalment, I am covering the remaining holy days beginning with Christ’s Ascension to the Feast of Corpus Christi. Why? Because in my research for the Reschen Valley series, which takes place in the former province of southern Tyrol, the church and the locals in my book are inseparable. Part of my research led me to integrating these feast days into certain scenes. In this instalment, I’m also sharing an extract from No Man’s Land, the first book in the series, which illustrates some of the unique rituals. And I’ve got some funny anecdotes for you in regard to my first introductions to Austrian and Tyrolean traditions.

Ascension - "Christihimmelfahrt"

I made my first trip to Austria in order to visit a friend whom I’d met while travelling through Canada and Alaska a year before. When I was in Europe, I came to visit him in western Austria and ended up staying for four months.

I happened to come on the first of May, which is Austria’s Labour Day. This was then followed by a string of post-Easter holidays, each of which was a day off from work and allowed my friend to show me around the Alps. I did not understand what all these holidays were (in America, it was certainly not an official bank holiday). So, I asked my friend, “What is ‘Christihimmelfahrt’? Which feast day is this?” To which he answered, “I don’t know what it’s called in English but it’s when Jesus came back to Earth, hung out with his apostles for a little while, did a few more tricks, then went back to heaven. A little like when Elvis left a building…” After I had finished wiping away the tears of laughter, I said, “Ascension. It’s called the Ascension.”

Ascension celebrates the return of Jesus Christ to his Father in heaven. The Church Feast of Ascension Day is celebrated on the 40th day of the Easter Circle, 39 days after Easter Sunday, which is why the feast always falls on a Thursday.

Many of the Tyrolean customs involve processions on the holy days. On Ascension, it is no different. In one village named Hall, near Innsbruck, they celebrate the feast day by raising a wooden picture of Christ ascending into heaven. There are trumpets and timpani. Once, when the rope broke and the figure fell and broke into pieces, the mayor immediately ran and got a bucket, tossed the pieces inside, tied it to the rope and let the good Lord rise in the bucket before the eyes of the joyful crowd.

Pentacost - "Pfingsten"

Whitsunday (or Pentecost) is one of the principal feasts of the Christian church, celebrated on the 50th day after Easter, to commemorate the descent of the Holy Spirit upon the disciples.

Depending on when Easter falls, Whitsunday is in late May or early June, and in Austria it is an official two-day (Sunday and Monday) holiday. A vast array of different kinds of celebrations abound, however they all deal with the central theme of “thanksgiving.” Thanksgiving for the fruit of the earth as an agricultural festival, and thanksgiving for the gift of the spirit flow together in a festival, celebrated in the marketplace and in the church.

For most rural areas, Whitsunday was the day when, for the first time that year, the livestock would be taken out to pasture. The first or the last animal would be decorated with a wreath of flowers and was the “Pfingstochse” (the Whitsunday Ox).

And there were also special foods. In Tyrol one celebrated with a big portion of “Maibutter” (whipped cream or butter with sugar and cinnamon) and young men of the village, the “Goaslschnalzer” would crack their whips in a display of skill and strength, and in a special rhythm, without getting them tangled up. I got to watch one of these when we were attended the “Almtage” – the first days on the alp – with my husband’s family in the Semmering mountainrange of Styria (where Arnold Schwarzenegger’s roots are).

Corpus Christi - "Fronleichnam"

The Feast of Corpus Christi was first celebrated in 1246 in the diocese of Liège as a celebration of the bodily presence of Christ in the altar sacrament.

At the centre of the celebration is the adoration of Christ present in the Eucharist as communion, i.e. as sacrificial food. Corpus Christi Day in Tyrol used to be known as The Holy Blood Day or Day of Arms. Ludwig von Hörmann described the following in an excerpt from a description of a rural Corpus Christi procession:

“It is really a wonderful poetic scene … The long procession of the prayers with the colourful waving flags and wreathed pictures, the flashing rifles and the picturesque gunner’s costumes, the flocks of children dressed in white and the wreathes of fresh flowers; all this set in the green meadows and ripening cornfields, behind them the dark forest, and above it the deep blue summer sky, in which the larks trill until they are frightened away by the crack and the volleys of gunfire – all this makes a moving impression on the unbiased observer.”

I was right on the fringes of the crowd where the priest stopped at one of the altars. What I did not know about, or even recognise during the procession, were the Schützen behind me, some four or five rows deep. They carried their rifles. When they raised their guns and fired their salutes into the air, I dropped onto all fours, just a few metres from the priest. I might have shrieked. There was a ripple of laughter and concern from the crowd, someone helped me to my feet, asked if I was okay, and then where I was from. “America,” I answered, still shaken. “Ah, yes. I see.” There was no time to try and explain anything further away.

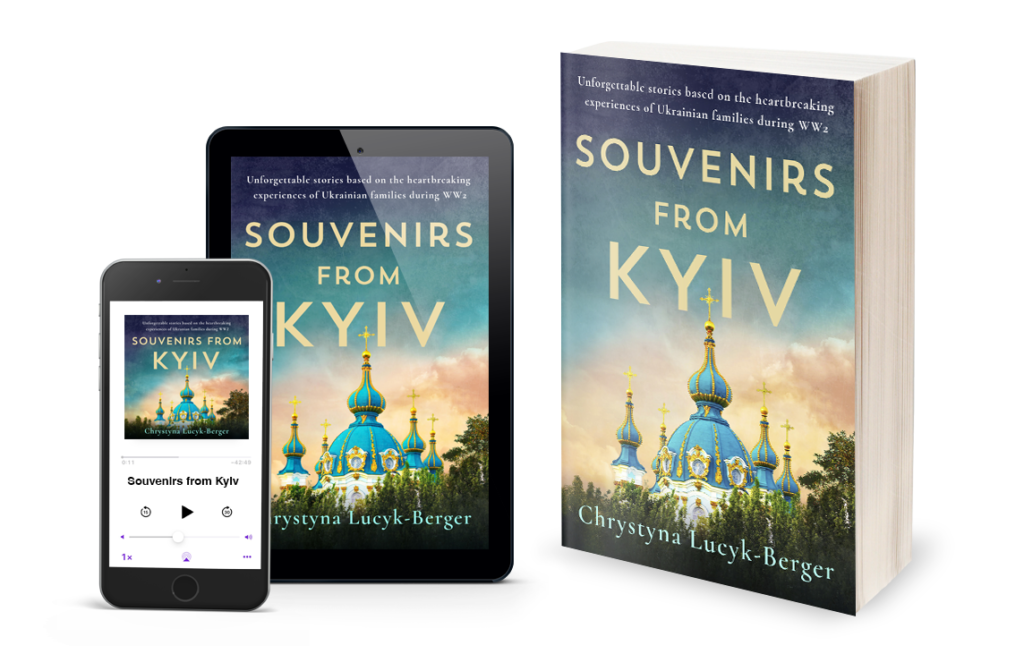

All these customs and many more have a long tradition in Austria and have been popular ever since. Here is an extract from No Man’s Land, where I incorporated some of the details from Corpus Christi.

From No Man's Land - Chapter 11

Before the final benediction, Jutta watched Florian move to the front of the church to stand with the rest of the Schütze, or what remained of the riflemen. The territorial regiment was now an omnium gatherum of older men and scarred war veterans. The brass band, too, had more women than men now.

To finish the Mass, Father Wilhelm faced the congregation. “And may the blessing of almighty God, the Father, and the Son, and the Holy Spirit, come down on you and remain with you forever.”

“Amen,” Jutta said.

She saw Florian pick up the Graun banner. Ironically, it featured the same colours as the tricolore of Italy: three vertical stripes in green, white, green, and a red eagle in the centre, its wings stretched out like Father Wilhelm’s robe when he raised his arms in blessing.

The regiment marched ahead. Florian smiled at her as they passed. Hans Glockner lifted his hand and waved at her, elbow at his hip. The altar boys led Father Wilhelm, who had the Book of Gospels raised above his head. As soon as the official part of the procession was outside, the sound of shuffling feet and muttered greetings from the townsfolk spilled together into the aisle between the two rows of pews. Sara and Alois joined her when they reached the door.

As the congregation spilled out onto the church square for the Corpus Christi procession, Alois pointed to beneath the oak tree.

“Look, Mother.”

Captain Rioba and two carabinieri she’d never seen before were lounging on the rim of the fountain. Reinforcements. They straightened up when Florian raised the gonfalon but did not step in to follow the procession.

Jutta took a close look at the three men. Captain Rioba was grey haired, looked gentlemanly and cultured, but he was also very military-like in his uniform and stature. In fact, all the Italians she encountered strutted about like peacocks on parade, as if they had truly won the war with their own two hands instead of just on paper.

The other two men were much younger. One had curly sand-brown hair and light-green eyes, giving him an ethereal look against his darker skin. She thought of Katharina. Had her Angelo been this handsome? If so, Jutta could understand the attraction. When she focussed on the third carabinieri, Jutta hardened. He looked of farmer stock, heartily fed and strong, with a broad forehead and wide-set eyes. He was watching the men at the front of the procession, and when Florian passed by with the gonfalon, this one spit into the fountain. Jutta grimaced. This man was cold, like her husband, and likely prone to brutality if need be.

Once everyone had gathered, the procession headed for the first of four altars placed around Graun, and the brass band played the “Tyrolean Eagle” march. At first the music was hesitant, as if with the three carabinieri looking on, the musicians were not certain whether their instruments would be confiscated like the regiment rifles a year ago. Only the official hunters were allowed theirs, like Johannes Thaler. Nobody said much about that aloud anymore, but they all felt it. The citizens in the valley felt stripped bare, helpless.

She stole one last glance at the three policemen before moving on with the others, and Alois, next to her, craned his neck to look back at the carabinieri. She felt as if predators were stalking them.

The congregation went from one altar to the next, stopping at each one for the prayers and blessings Father Wilhelm led. Florian had built the altars from fresh saplings and pine, and some of the women had decorated them with flowers. As the procession came full circle and returned to the square, Jutta tore herself from the crowd. Everyone would head to the Post Inn after the last prayers and blessings had been given, but there would no longer be a forty-gun salute that signalled the opening of the festivities.